By Alex Gordon

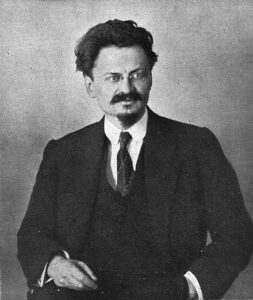

Bronstein, who became known as the Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky, owes his reputation as an arsonist, destroyer and symbol of the revolution to his volcanic energy, his leadership of the October coup, his creation of the Red Army, his complicity in the organization of the “Red Terror” and his numerous vivid public speeches filled with anger, passion and conviction as if he were a biblical prophet.

On January 7, 1918, historian Shimon Dubnov predicted the ominous role of Trotsky’s activities in the unfolding of a new kind of antisemitism in Russia – the protest against the terror of Soviet power: “We will never be forgiven for the role played by the Jewish figures of the revolution in the Bolshevik terror. Lenin’s associates and collaborators – the Trotskyites and Uritskyites (Moses Uritsky- chairman of the Cheka, the secret police). – cast a shadow even over him. […] Then they will speak about it openly, and antisemitism will be deeply rooted in all strata of Russian society.”

Much has been written about Trotsky, but it is not easy to get to his Jewish complexes. How did the life path of the “red prophet” begin? “We did not know need, but we did not know the bounties of life either. […] It was a grayish childhood in a petty-bourgeois family, in the countryside,” Trotsky wrote in his autobiography My Life (1929). “By the indefatigable, cruel, ruthless to himself and to others labor of initial accumulation my father rose upward,” noted Trotsky in the first chapter of his memoirs “Yanovka.”

David Leontievich Bronstein became one of the victims of the realization of the ideas of the revolutionary son. The son mercilessly and without a note of bitterness describes the robbery and suffering of his father: “The October Revolution caught my father a very wealthy man. My mother died back in 1910, but my father lived to see the power of the Soviets. In the midst of the civil war, which was especially long rampant in the south, accompanied by a constant change of authorities, seventy-five-year-old old man had to walk hundreds of kilometers to find a temporary shelter in Odessa. The Reds were dangerous to him as a large property owner. The Whites persecuted him as my father. […] The October Revolution took from him, of course, everything he had gained.”

The leader of the revolution felt his Jewish origin from his early childhood: “The ten percent “numerus clausus” [“Numerus clausus”, “closed number” in Latin, is one of many methods used to limit the number of Jewish students who may study at a university] for Jews in state educational institutions was introduced in 1887. It was almost hopeless to get into the gymnasium: one needed patronage or bribery. In the fall I took the exam for the first class of the St. Paul’s Real School.” A Jew who had experienced the humiliations of the Jewish pogroms or had heard about the horrors of the Jewish pogroms, certainly felt the disenfranchised position of the Jews regardless of their class affiliation. Like other future Jewish revolutionaries, Trotsky grew up as a compressed spring of hatred for the authorities, but cultivated a class approach in preference to a national one.

In 1903, at the Second Congress of the RSDLP in London, Trotsky criticized the Jewish socialists of the Bund for demanding cultural autonomy in the socialist movement. The idea of assimilating the Jews was his fix-it idea. That same year in Basel, at the Sixth Congress of Zionists, Trotsky called Herzl a “shameless adventurer.”

In 1907, Trotsky escaped from exile in Siberia, where he was sent for his leadership role in the 1905 revolution. Jewish pogroms were raging in Russia. The Mendel Beilis case in Kiev (1911-1913) caught Trotsky in Vienna. The trial accused not only Beilis, but also Jewish customs and holy books. Trotsky was shocked. He wrote much about the case, but could not utter the fact that the Jewish people were put in the dock. Under the influence of the Beilis case, in August 1913 Trotsky published three articles under the title The Jewish Question in the newspaper Kievskaya Mysl. In the publications he deviates from the Marxist class approach and puts the national question in the foreground. The author was disturbed by the oppression of the Jews in Romania. The article on antisemitism in Romania subconsciously expresses Trotsky’s worries and fears about Russian antisemitism.

Trotsky, however, did not solidarize with the Jews. The writer Alexander Kuprin, who hated him for his leading role in the establishment of Soviet power, relayed a story he heard about the leader, with his own comments (1920): “It is said that once a Jewish delegation consisting of the most ancient, honorable and wise elders appeared to Trotsky. They eloquently, as only very intelligent Jews can do, persuaded him to turn from the path of blood and violence, proving with figures and words that the chosen people suffer most of all from the policy of terror. Trotsky listened to them impatiently, but his reply was as short as it was dry:

“You have addressed yourself to the wrong place. The private Jewish question does not interest me at all. I am not a Jew, but an internationalist.”

“And yet, he himself was deeply mistaken in renouncing his Jewishness,” Kuprin continued. “He is more Jewish than the deeply honored and renowned Tzadik of Shpola [meaning Rabbi Aryeh-Leib of Shpola, 1724 – 1811.]. I will say sharper: by virtue of the mysterious law of atavism, his character contains real biblical features.”

Kuprin, who wrote the touching story Gambrinus, full of sympathy for the protagonist, a Jewish violinist, and signed a letter in defense of Beilis, condemned Trotsky for his departure from Jewishness and yet was sure that his character contains “biblical features,” that he was “more Jewish” … Kuprin, a fine artist, notices the duality of the hero, hidden from himself: The specter of internationalism roamed Trotsky’s mind, suppressing thoughts of the Jewish question.

Trotsky wrote brilliantly, was an outstanding orator, and ignited crowds during speeches, although he spoke with a slight Jewish accent. Despite a certain provincial rusticity of a villager, he behaved like an international celebrity, was defiantly arrogant and a poseur. Trotsky appealed to the masses and repelled his party comrades. He wore a well-cut khaki-colored half-military suit, high soldier’s boots of officer’s pattern. The chief warrior of the revolution, the organizer and first commander of the Red Army had nervously moving hands with long fingers and hard, intelligent eyes covered by pince-nez. He was a sharp, strong, determined, courageous and cruel man and the envy of his associates. Trotsky posed before the mirror of history and imagined himself as Napoleon and Messiah for the proletariat.

The demonization of the Bolshevik coup reinforced Trotsky’s satanic image, to which the allegation of the devilishness of Jewry was naturally fitted. In 1926 Trotsky, who was engaged in an unequal struggle with Stalin in the Moscow party organization, encountered manifestations of antisemitism on the part of his Bolshevik comrades. In a letter to another Bolshevik leader, Nikolai Bukharin, he asks: “Is this possible? Is it possible that in our party, in the workers’ cells, here in Moscow, people resort to antisemitism with impunity? Is it possible?” Pain, amazement, disappointment and shock resound in Trotsky’s words. He discovered what he had been chasing away for many years: his fellow party members, who were supposed to be internationalists but turned out to be antisemites, saw and disliked the Jew in him. Trotsky, who stifled the Jew in himself, was horrified that others, unlike him, have not forgotten his Jewish origins.

In the book My Life Trotsky noted: “The question of my Jewishness began to gain importance only with the beginning of the political harassment against me. Antisemitism raised its head at the same time as anti-Trotskyism.” He allowed himself to notice antisemitism, but as something limited, petty, not peculiar to the USSR and used only to fight an unwanted leader. Trotsky underestimated the significance of Stalin’s antisemitic methods of fighting the opposition, which included many Jews. In the second half of 1927, the slogan “Beat the opposition!” was launched, reminiscent of the well-known and popular in Russia slogan “Beat the Jews!”

On November 7, 1927, the opposition tried to stage protest demonstrations in Moscow and Leningrad on the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. Stalin’s police easily dispersed the rallies. Trotsky was prevented from speaking. Cries were heard in the crowd, “Down with Trotsky! Jew! Traitor!”

On September 14, 1929, Trotsky was expelled from the USSR to Turkey. In 1936, during the trials that led to the conviction and execution of Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, Trotsky learned from Norway about the outbreak of antisemitism in the USSR initiated from above. On January 18, 1937, he wrote: “If the revolutionary wave revives the finest feelings of human solidarity, Thermidorian reaction will stir up all that is low, dark and backward in this conglomerate of 170 million people. To reinforce its dominance the bureaucracy will not even hesitate to resort in a barely disguised way to chauvinistic tendencies, above all antisemitic tendencies. The most recent Moscow trial, for example, was staged with a slightly disguised scenario, presenting the Internationalists as lawless, and lawless Jews who are capable of selling themselves to the German Gestapo.”

Trotsky discovered antisemitism where, according to his theory, it should not have existed. In the article Thermidor and Antisemitism (1937) he wrote: “During the last Moscow trial, I noticed in one of my statements that Stalin exploited antisemitic tendencies in the country in his struggle with the opposition.” Trotsky learned of the condemnation of Zinoviev and Kamenev to death. Did he realize that he too was sentenced to the same punishment?

Unlike his predecessors and co-religionists Marx and Lassalle, Trotsky never spoke out against the Jews, but against the “petty-bourgeois” elements. He defiantly called himself an “internationalist,” banished thoughts of Jewishness, his own and others’, but sounded the alarm over the possible rise to power of the Nazis. He was concerned about the danger of a Nazi regime for the proletariat, not for the Jewish people.

Trotsky warned: “The coming of the National Socialists to power would mean, above all, the extermination of the color of the German proletariat, the destruction of its organizations, the eradication of its faith in itself and in its future.” Trotsky was wrong: the Nazis did not exterminate “the color of the German proletariat,” but the Jews of Germany and Europe, not the color of the Jews, but all of them.

In 1937, realizing more and more the threat of Nazi power, Trotsky hesitated to take an exclusively class-based approach. He began to realize that Marx, Lenin and he were not quite right in seeking to impose assimilation on the Jews. His confidence in the correctness of the struggle against Jewish assimilation is replaced by doubts and disappointment at the unattainable internationalism. Reality refutes the traditional Marxist approach that dictates the fusion of Jews with other peoples: “During my youth I was rather inclined to the prediction that the Jews of different countries should assimilate and that the Jewish question would thus disappear in a quasi-automatic way. The historical development of the last quarter century has not confirmed this prospect. Decaying capitalism has turned everywhere to violent nationalism, of which antisemitism is a part. The Jewish question has assumed threatening proportions in the most highly developed capitalist country in Europe, Germany.”

In 1938, Trotsky’s anxiety about the fate of the Jews grew, and the purely class-based, Marxist approach disappeared, giving way to a national approach: “The victory of fascism in France would mean a colossal strengthening of reaction and a monstrous growth of violent antisemitism throughout the world. […] The number of countries that expel Jews is growing unceasingly. The number of countries able to accept them is decreasing. […] One can easily imagine what awaits the Jews once a future world war breaks out. But even without war, the future development of world reaction definitely means the physical destruction of the Jews.” Trotsky’s prediction, which was not based on a Marxist approach, turned out to be sadly accurate.

After Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany, on December 22, 1938, Trotsky wrote: “The Jews of various countries have created their own press and developed the Yiddish language as an instrument of adaptation to modern culture. Thus, the fact that the Jewish nation will preserve itself for the whole coming epoch must be taken into account. Now a nation cannot properly exist without a common territory.” This remark lacked a Marxist approach and a division between the Jewish bourgeoisie and the Jewish proletariat. Trotsky concluded that territory is needed to solve the Jewish question. His internationalism experienced hesitation and his excitement about the fate of the Jews grew.

But he rejected the then-existing territorial solutions to the Jewish question: “Palestine is a tragic mirage, Birobidzhan [the Jewish Autonomous Region created by Stalin in the Far East of the USSR.] is a bureaucratic farce. […] The conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine is becoming more tragic and more threatening. I do not believe at all that the Jewish question can be resolved within the framework of decaying capitalism and under the control of British imperialism.” Unwilling to hear of the existence of Jewry as an independent nation, Trotsky used the national terminology he had previously denied in his struggle with the Bund and the Zionist movement and allowed the acquisition of territory by the Jewish people.

“The Red Prophet” saw the world in a red light and underestimated the strength of the Jewish people’s desire for independence. Trotsky left the life he saw through the lenses of socialist glasses. The permanent revolution he believed in did not take place.

Trotsky developed the idea of Marx’s world socialist revolution and Parvus’s permanent revolution. National revolution in Russia was a petty idea for him. It would sound more natural in the mouth of a representative of an indigenous nation. Trotsky could only solidarize with a supranational revolution. He needed a world scale, a world revolution, occurring as a chain reaction in one country after another. Under the aegis of the world revolution, which is constantly capturing new nations, Trotsky’s enormous Jewish energy, subconsciously directed by the representative of the oppressed nation against its oppression and oppressors, could be disguised.

Since the revolution is permanent, with a constant increase in the number of participating nations, its accomplishment does not cast a shadow on the Jew Trotsky, who essentially wants his own liberation in his own country (and later in all the countries where he lived) and passes off his local goal as an international one. Like many prominent representatives of emancipated and self-emancipating Jewry, Trotsky was gripped by megalomania, which is the flip side of the Jewish inferiority complex. His overactive participation in the socialist and communist movement was the result of his escape from his burdensome nationality and the consequence of his assimilation into the universal non-Jewish world. The break with national traditions turned Trotsky into a radical acting in the name of universalism and against Jewry. He shook off his Jewish affiliation with great zeal and appeared sincerely devoted to the international proletariat.

Despite his alienation from the Jewish people, his dismissal of them and his service to the “world proletariat,” Trotsky was identified with Jewry. He disliked the nation out of whose problems his motivation to act for the world revolution was formed, but in the last years of his life he was seized with a thrill of concern for the fate of the Jewish people, whose belonging he had masked, suppressed and concealed.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and the author of 10 books. He has been published in 91 journals in 17 countries in Ukrainian, Russian, Hebrew, English, French, and German.

There is no question that genetically speaking, Trotsky was a Jew. But personally and culturally, he emphatically denied any connection with the Jewish people. Quoting from my book Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime:

Trotsky—the satanic “Bronstein of Russian anti-Semites”—was deeply offended whenever anyone presumed to call him a Jew. When a visiting Jewish delegation appealed to him to help fellow Jews, he flew into a rage: “I am not a Jew but an internationalist.” He reacted similarly when requested by Rabbi Eisenstadt of Petrograd to allow special flour for Passover matzos, adding on this occasion that “he wanted to know no Jews.” At another time he said that the Jews interested him no more than the Bulgarians. According to one of his biographers [Baruch Knei-Paz], after 1917 Trotsky “shied away from Jewish matters” and “made light of the whole Jewish question.”