By Sheila Orysiek

SAN DIEGO–I have read that Jews are very good at analysis – taking apart a problem, looking at it – analyzing its segments, and recomposing it. This comes from centuries of studying Talmudic text, group discussion, and lifelong dedication. I am not a student of such scholarship, but I did have a couple of grandfathers and great grandfathers who spent their lives in such study. So, maybe their genes infiltrated mine and stood me in good stead in ballet class. They surely would have been surprised how their legacy was used.

SAN DIEGO–I have read that Jews are very good at analysis – taking apart a problem, looking at it – analyzing its segments, and recomposing it. This comes from centuries of studying Talmudic text, group discussion, and lifelong dedication. I am not a student of such scholarship, but I did have a couple of grandfathers and great grandfathers who spent their lives in such study. So, maybe their genes infiltrated mine and stood me in good stead in ballet class. They surely would have been surprised how their legacy was used.

Ballet class is divided into two major sections. The first half takes place at the barre and is a slow warm-up. The second half is in the center of the room where dance combinations and technique are put into practice. The vocabulary of ballet movement is sub-divided into several major categories: adagio – slow; allegro – fast; waltz – 3/4 time and usually large sweeping steps and finally grande pas – the largest jumps and turns in the repertoire. After about ten years of schooling, I felt that I was in some control of each of these elements. That is, until the day Mr. Davis walked into the classroom.

Ballet class is divided into two major sections. The first half takes place at the barre and is a slow warm-up. The second half is in the center of the room where dance combinations and technique are put into practice. The vocabulary of ballet movement is sub-divided into several major categories: adagio – slow; allegro – fast; waltz – 3/4 time and usually large sweeping steps and finally grande pas – the largest jumps and turns in the repertoire. After about ten years of schooling, I felt that I was in some control of each of these elements. That is, until the day Mr. Davis walked into the classroom.

Mr. Davis was a large imposing man who strode to the front of the room with force and flair. As it usually happens with a new teacher, all of us in class that day made a special effort to understand what he wanted and tried our best to execute it. Generally it takes a while to feel comfortable with the style of a new teacher; to incorporate the demands into an already assimilated store of knowledge that each student possesses. This was by no means a beginner class. All of us had been dancing many years and were already at varying levels in the professional hierarchy. Still a new teacher is like trying on new clothes, it takes time to wear them gracefully.

The first half of class went well. Then Mr. Davis announced that he felt the allegro component of ballet was sadly under-taught and he hoped to rectify that neglect. He rattled off a string of pas (steps), and instructed the pianist for the correct tempo. The combination he wanted was sixty four beats in length with no repeated sequences, and as many as three steps per beat; all at breakneck speed. The class came to a halt as if we had hit a brick wall – as well we had. When some complained that the music was too fast, he informed us that we were too slow.

Mr. Davis never demonstrated, at that technical level it is usually not necessary. Also, he would never say the combination more than once. There was no rehearsal and no slow work up to the tempo required. It was therefore necessary to commit to memory instantly sixty four counts of instruction, transfer that to the body and dance it full out the very first time. Everyone failed. I was in despair. Worse yet, Mr. Davis was designated to be our teacher for quite some time, he had a signed contract.

I studied the problem. First was the difficulty of committing to memory on only one hearing the string of dance pas (steps). If I couldn’t remember it, how could I begin to perform it? He even spoke at an abnormally fast speed! Another problem was that as a tall dancer it takes a bit more time for my longer foot to peel off the floor than for a shorter dancer. That is always a problem; a taller dancer just has to move faster. After every class as I drove home I painstakingly tried to reconstruct the bits I could remember. Then when I got home I practiced without pause to the fastest tempo I could find in my collection of music. No matter how hectic the rest of my schedule, I never neglected this post mortem work. I worked on this seven days a week. Yes, we had a Sunday class and I never missed any of it.

As the days and weeks went on our class shrank in size. Some dancers were reduced to tears. Others simply left. It was almost impossible to find another ballet class at the professional level in San Diego. Beginner classes are everywhere, but not the higher levels. Some people in our class always seemed to have to go to the rest room or left early when we reached the allegro portion of the day’s lesson. After a year only a handful of us struggled on. It had become a personal challenge to me.

Mr. Davis called his allegro combinations “Chinese puzzles” and indeed my mind and body agreed. His demanding choreographic patterns were a wonder of intricacy. If a certain step was usually performed as a forward motion, he would be sure to ask for it moving backward. If a certain sharp turn was usually done inwardly, he wanted it outward. It was all perverse, almost demonic. Even the pianists had difficulty and we went through several before one was found who could perform up to the teacher’s demands for speed.

After a year I was still working on a daily basis on the portions of the allegro I could remember. Then gradually I found the memory problem had ceased to be a problem at all. It took me two more years to master the speed. But each step, as blindingly fast as it had to done, still needed the correct accompanying arm patterns, head positions, and maybe even a smile.

It wasn’t until the end of three years, with just a few of the survivors of the original class left that it all came together for me. One day, Mr. Davis stopped the class, looked at me and pointed, “Do it!” he commanded. The music started and I was off in a dash. My feet were no longer part of me; they had a life and force of their own. My arms hit and flowed from one pattern to another. The accents and syncopation were there. A smile was on my face. As I finished, my reward from him was a sharp nod and half of a smile. Not to be outdone by this understated acknowledgment of my accomplishment, I said to him, “May I do it faster?” With a glint in his eye he nodded to the pianist and off I went again. Later in class as he walked by me, he whispered, “That was very good!”

I accepted this in silence. I remained silent until I was safely in my car at which point I shouted “YES!!” I think my grandfathers and great grandfathers would have been proud.

*

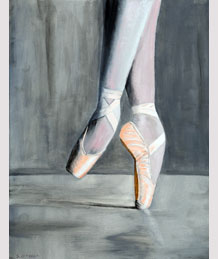

The illustration, “Sur La Pointe,” is after a painting by dance columnist Orysiek, who may be contacted at orysieks@sandiegojewishworld.com