By Alex Gordon

HAIFA, Israel — In 1917, Boris Pasternak, the future Nobel Prize winner for literature, published a collection of poems titled Over Barriers. What barriers did the poet not write about?

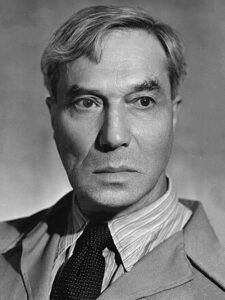

Boris Pasternak was born on February 10, 1890 in Moscow, in a Jewish family of artist Leonid Pasternak and pianist Rosalia Kaufman. In the spring of 1912, fascinated by neo-Kantianism and the daughter of the wealthy tea merchant Wisssotzky, Ida, he arrived in Marburg, at the school of the neo-Kantian philosopher Hermann Cohen, who offered to supervise his doctoral dissertation.

Boris, however, interrupted his studies and returned to Russia. His departure is described in literary criticism and by the poet himself as Pasternak’s decision to break with philosophy and devote himself entirely to poetry. However, the poet seems to have concealed one circumstance.

Pasternak’s feelings about Jews and Jewry in the first 22 years of his life are ̶ negative: humiliation, oppression, pogroms. A different vision of the Jewish problem was revealed to him in Marburg. Pasternak encountered Jewish thinking for the first time in his life: Cohen’s teachings were based on the ethics of Judaism. Plagued by Jewish complexes in Russia, he was apparently shocked by the position of the Jewish thinker and rejected Cohen’s offer to continue his philosophical studies.

In his memoirs, Pasternak called his teacher “the genius Cohen.” However, he was silent on the role of Cohen’s personality and views in his departure from philosophy, his departure from Germany, and his even greater distance from Jewishness. As he did thereafter, Pasternak applied the Freudian technique of “displacing” unpleasant feelings, hiding and banishing the Jewish theme.

The poet expressed his attitude to his Jewish origins in a letter to the writer Maxim Gorky (1928): “I, with my birthplace, with the environment of my childhood, with my love, my ambition and inclination, should not have been born a Jew. […] Winds of anti-Semitism passed me by and I never knew them.” Could Pasternak have been unaware of the “winds of anti-Semitism”? In 1900 he was not admitted to the Fifth Moscow Gymnasium because of the Numerus Clausus (“closed number,” amount fixed as maximal number in the admission of Jews to Universities in Tsarist Russia). In 1905 ̶ 1906 a wave of post-revolutionary pogroms swept through Russia, and in 1906 a congress of Black Hundred organizations was held in Moscow. In 1908 Pasternak entered Moscow University, humiliated by the Numerus Clausus. In 1911 the Beilis trial began, shaking the Jewish and non-Jewish intelligentsia of Russia. Pasternak subconsciously guarded himself against disturbing reflections about his Jewishness.

Pasternak visited his parents, who had moved to Berlin, in late 1922 ̶ early 1923. In a letter to his brother in Moscow on January 15, 1923 Boris supported the plans of Alexander, who wanted to marry a Russian girl: “I sincerely wish that you were able to marry Irina. […] That this family is not Jewish, of course, only better, not worse. You know my sympathies and antipathies.”

In a letter to his cousin Olga Freidenberg on October 13, 1946 Pasternak said that he had begun to write a novel in which “I settle accounts with Jewry, with all shades of nationalism (and in internationalism), with all shades of anti-Christianity.”

The novel Doctor Zhivago. Pasternak attacks Jewry with the help of the novel’s hero, the Jew Michael Gordon: “How could they [Jews] let escape from themselves the soul of such absorbing beauty and power [Jesus], how could they think that beside its triumph and enthronement they would remain as an empty shell of this wonder, once discarded by them? […] The complete and undivided victim of this element is Jewry. The deadening necessity of being and of remaining a people is placed on him by national thought. […] In whose benefit is this voluntary martyrdom, who needs so many innocent old men, women and children, so delicate and capable of kindness and cordial fellowship, to be covered with ridicule and bled for centuries!” For the poet, Jewry is an “empty shell” of Christianity, a dead nation whose national outlook paralyzes its development. Pasternak places the blame for the suffering of the Jews on themselves.

In Germany, where the poet’s parents lived for 17 years, the baptism of Jews made less and less sense to equalize them with non-Jews, being reduced to nonsense under the Nazis. Racism in Judophobia prevailed over its religious content. The racism that prevailed deprived Pasternak’s critique of Jews who had turned away from Christianity of all meaning. Jews were doomed to be victims of pogroms even if they had embraced Christianity. Pasternak’s condemnation of the Jews for their religious priorities seemed like an anachronism, an argument that had to do with the mid-nineteenth century and lost its meaning in the first third of the twentieth century.

In Russia, as in Germany, the religious dispute about which Pasternak writes in the novel has given way to “an accusation of blood. The racial danger was noticed by Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev in his article The Jewish Question as a Christian Question (1924): “Racial anti-Semitism, carried to completion, turns into enmity toward Christianity. […] A Christian cannot profess racial anti-Semitism because he cannot forget that the Son of God was a Jew by humanity, that the Mother of God was a Jew, that the prophets and apostles were Jews and that many of the early Christian martyrs were Jews. The race that was the cradle of our religion cannot be declared an inferior and hostile race. […] The attitude toward Jewry is a test of the strength of the Christian spirit. This test has fallen on the Russian people in the highest degree. And with bitterness it must be realized that the Russian people cannot withstand it very well.”

In his novel Doctor Zhivago, Pasternak says through the mouth of Lara: “The people who once liberated humanity from the yoke of idolatry and now devote themselves in so many ways to freeing it from social evil, are powerless to free themselves from themselves, from allegiance to an outmoded pre-flood name that has lost its significance, cannot rise above themselves and dissolve without trace among others, whose religious foundations they themselves have laid and which would be so close to them, if they knew them better.”

For the poet, the Jews are a “pre-flood name,” an “outmoded” nation, a religion backward in comparison with Christianity, blinded fanatical people in bondage to religious customs, senselessly rejecting the “true” religion ̶ Christianity. He believed that Jews should free themselves from Jewishness, assimilate, “dissolve among the rest without a trace”.

Pasternak believed that the Jews’ “erroneous” rejection of Christianity was due to their ignorance of its basics. This approach differed from that of the Russian philosopher, Christian theologian, and publicist Vladimir Solovyov, an expert on the Talmud. During the pogroms of the early 1880s, Solovyov published an article entitled Jewry and the Christian Question (1884).

He noted: “The Jews have always treated us as Jews; we Christians, on the contrary, have not yet learned to treat Judaism as Christians. They have never broken their religious law with respect to us, but we have constantly broken and are still breaking the commandments of the Christian religion with respect to them.” In the pogroms the commandments #6 (You shall not murder), #8 (You shall not steal), #10 (You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife or anything that is your neighbor’s) were broken. Unlike Pasternak, Solovyov put the blame for the alienation of the Jews from Christianity on the Christians, not on the Jews.

Pasternak glosses over the pogroms and their destructive role in Jewish and Christian history. He withdraws from the Jewish question, removes from consciousness the figure of Cohen, the pogroms in Russia, and with this displacement of the Jews he goes through World War II, in which a third of the Jewish people were exterminated. He did not react to the news of the Holocaust.

Pasternak’s dismissal of the Holocaust is evidenced by the story of his meeting in the winter of 1944 in the editorial office of Literature and Art with the Jewish poet Avraham Sutzkever, a prisoner who had escaped from the Vilna ghetto, a witness at the Nuremberg trials and later a recipient of the State Prize of Israel. Pasternak listened to Sutzkever’s account of the persecution of Jews, and 13 or 14 years later denied the encounter in a letter: “I do not remember that I was acquainted with Sutzkever; on the contrary, I have the feeling that I wanted to avoid this meeting because of a terrible shame, awe and horror before this martyr.”

In his memoirs, Sutzkever described how he introduced Pasternak to his poems in Yiddish and how the latter promised to translate them into Russian. The fact of their acquaintance is evident from an interview that the Israeli writer Yaakov Beser conducted with the poet in 2001. The interviewer also asked Sutzkever about his acquaintance with Pasternak:

– Did you also meet Pasternak?

– Yes, I wrote a poem about it. You haven’t read it? Too bad, it’s one of my best poems.

Pasternak’s “Nobel” novel, Doctor Zhivago, was written after the Holocaust. A great poet, a subtle man, Pasternak not only cut himself off from Jewry, but he also did not change his moral point of departure and ignored the tragedy of the extermination of Jewry. Of course, he was not supposed to write about what happened later in his novel about the Revolution and the Civil War, but the Holocaust did not affect his attitude toward Jewry. Pasternak “pushed” the Holocaust and Sutzkever out of consciousness, just as he had previously removed the pogroms and the Jewish figure of Cohen.

While Pasternak was writing Doctor Zhivago, the “cosmopolitan case” took place, Jewish writers and members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were shot, the “poison doctors case” took place. These were pogroms devoid of religious content. However, the poet did not change his attitude toward the Jewish problem, ignoring the repression of Jews in 1948-1953.

The poetess Maria Petrovykh, who translated Peretz Markish’s poems from Yiddish, spoke to him about those persecutions of Jews. Michael Landman, a poet and translator who worked at Haifa University, left a memoir of his reaction to these events by the poetess: “One of his ‘oddities’ even she could not justify: his attitude towards Jewry. One day, during the years of rampant anti-Semitism, when the elite of the Jewish Soviet intellectuals were being eliminated literally before the eyes of the world, Petrovykh, when she met Pasternak, talked about what was happening. […] Pasternak interrupted her irritably:

– This is not my train carriage. Leave me out of this.

Maria Sergeyevna was shaken to the core. She, a non-Jew, was more hurt by what was happening than he, a Jew.”

Pasternak, an outstanding translator, translated poems from dozens of languages. Jewish poetry was an exception. About Pasternak’s refusal to translate Peretz Markish’s poems, Simon, Markish’s son said in 1997: “The first time I came to Anna Akhmatova was in May 1956. Six months before that, my father, the Jewish poet Peretz Markish, who was executed on August 12, 1952, among the leaders and collaborators of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, had been posthumously rehabilitated. Immediately my mother, Esther Markish, began preparing a collection of my father’s poems in Russian translations, which, of course, I wanted to adorn with the most famous names of the translators. First of all, my mother turned to Pasternak: he knew my father well enough. Pasternak’s answer was swift and categorically negative: everyone who loves and appreciates him, he wrote, should encourage him to engage in his own poetry, and not be drawn into new translations.”

It was not about another translation, but about the “resurrection” of the slandered creator of repressed Jewish literature, about participation in the restoration of an exterminated culture.

After his meeting with Cohen in Marburg, Pasternak wrote to his father: “Something about all this [Cohen’s behavior] is unsympathetic to me […] Neither you nor I, we are not Jews; not only do we voluntarily and without any shadow of martyrdom undertake everything that this happiness obliges us to do, […] but this does not make me any closer to being a Jew. Do as you like.”

The poet adds “do as you like,” for he is not sure that his father would agree that “we are not Jews.” These words reveal Cohen’s “Jewish footprint” in Pasternak’s life, his rejection of the Jewish thinker. The poet’s father, Leonid Pasternak, died in Oxford on May 31, 1945. Six months after his nationally-minded father’s death, on November 30, 1945, his son began writing a novel, Doctor Zhivago, in which he intended to “settle a score” with his father’s people.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.