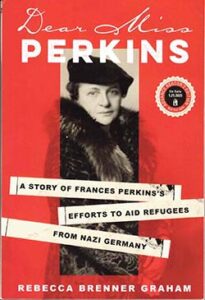

Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins’s Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany by Rebecca Brenner Graham; New York: Citadel Press Books imprint of Kensington Publishing Corp.; © 2025; ISBN 9780806-543178; 280 pages plus acknowledgment and notes; $29; publication date: January 21, 2025.

SAN DIEGO – Struggling against American xenophobia, racism, and antisemitism in the 1930s, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins—the first woman to serve in a President’s Cabinet – sought in several ways to spare German Jewish refugees from annihilation by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

SAN DIEGO – Struggling against American xenophobia, racism, and antisemitism in the 1930s, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins—the first woman to serve in a President’s Cabinet – sought in several ways to spare German Jewish refugees from annihilation by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

Up to 1940, when it was transferred to the Justice Department, immigration was the responsibility of the U.S. Labor Department. Since 1917, American law required immigrants to be denied entry if they were likely to become a public charge. So, in an effort to save German Jewish children, Perkins, an Episcopalian, embarked upon a program that would have enabled individual immigrants – or their sponsors – to put up $500 bonds to assure that they would not go onto the relief rolls. However, the program permitted only a trickle of children between the ages of 6 and 16 to enter the country.

To do more, for example, matching the 10,000 children Britain took in during its kindertransport program, would run afoul of the isolationists and restrictionists in Congress, some of whom argued that before the United States does anything to improve the lives of German Jewish kids, it should take care of children in the slums of big cities who often roamed the streets without visible means of support.

Arch-conservatives in the Congress were angry with Perkins for not summarily deporting Harry Bridges, the Australian-born president of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), arguing that she could have instructed immigration authorities overseen by her department to deport Bridges, whom they suspected of being a Communist agent after he ordered strikes at major American ports.

When Perkins refused to deport him, a bill of impeachment was drawn up against her. Although it did not pass the House, the impeachment motion dissipated much of Perkins’ clout. She, in essence, no longer had the political capital to fight for a massive expansion of the bonding program for refugee children.

What she could do was intervene in individual cases in which refugees, already in the United States, were required to leave the United States by a certain date. She could—and did—persuade her underlings on a case-by-case basis to extend the visas for such individuals. She received many “Dear Miss Perkins” letters requesting her intervention, some of which author Graham quoted verbatim in the book which draws its title from this portion of Perkins’ career.

Another effort that went nowhere was to settle German Jewish refugees in Alaska, then a U.S. territory not subject to the same laws as the continental 48 states. The advantages of such a scheme might have been to build up Alaska’s skilled workforce and economy. Beefing up the territory’s population might also have strengthened its defenses against Japan, which was perceived as a potential wartime adversary nearly a decade prior to that nation’s attack on Pearl Harbor. However, both the indigenous Alaskans and the White settlers opposed such a policy – the native Alaskans fearing even more loss of their ancestral lands and the Whites expressing distrust of foreigners, especially Jews.

Perkins’ humanitarianism was no match against Americans’ xenophobia and antisemitism.

Perkins retired from government soon after Franklin D. Roosevelt died and Harry S. Truman became the President. Graham said her contributions were largely forgotten although scholars and hometown museum enthusiasts researching FDR’s three full terms in office and a partial fourth term recorded enough about Perkins’ life and career to spark Graham’s interest in telling the Labor Secretary’s story.

Graham’s research also told how immigration law was modified in subsequent years. It still favors White immigrants, she said, but Jews have since been accorded White status by majority-Christian America. An indicator of this trend was frequent and common references to American’s “Judeo-Christian” heritage in popular literature. An assessment of America’s role in the Holocaust –including its failure to come to the aid of Hitler’s victims—is now generally understood as a black mark in America’s history.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.