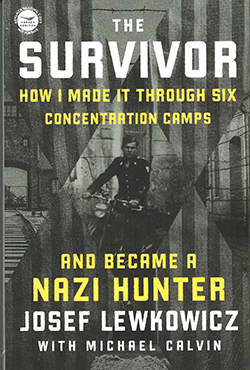

The Survivor: How I Made It Through Six Concentration Camps and Became a Nazi Hunter By Josef Lewkowicz (with Michael Calvin); New York: Harper Horizon, an imprint of HarperCollins Focus LLC: © 2025; ISBN 9781400-249527; 241 pages; $29.99; Publication Date: January 27, 2025.

SAN DIEGO – Josef Lewkowicz was 16 years old when he was rounded up by the Nazis and sent with his father to a site where they laid the groundwork for the Plaszow Concentration Camp, one of six where Lewkowicz was imprisoned over a period of three years. His mother and siblings were not so lucky; they were selected to die in the gas chambers. He lost touch with his father whom he later learned had been transferred to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp in Bavaria where he died of an unknown cause.

SAN DIEGO – Josef Lewkowicz was 16 years old when he was rounded up by the Nazis and sent with his father to a site where they laid the groundwork for the Plaszow Concentration Camp, one of six where Lewkowicz was imprisoned over a period of three years. His mother and siblings were not so lucky; they were selected to die in the gas chambers. He lost touch with his father whom he later learned had been transferred to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp in Bavaria where he died of an unknown cause.

Orphaned, Lewkowicz’s strategy for survival was based partly on his small stature which allowed him to stand practically unnoticed in formations. He remembered his father’s advice: “If they beat you, do not fight back. Bow your head down and take it. Quiet your enemy by your obedience.” At the Melk Concentration Camp, a satellite camp of the infamous Mauthausen camp, where prisoners were pushed to their deaths from the cliff above a quarry, Lewkowicz curried favor with Julius Ludolf, the camp commandant.

When the opportunity arose, he told Ludolf (in German), “Dear Sir, Camp Commandant, I will shine your boots, so they shine like the sun.” Ludolf agreed, sending Lewkowicz under guard to his home, where he shined and shined his boots, and then asked what other service he could render. Satisfied, Ludolf converted Lewkowicz to a household servant. When Lewkowicz went back and forth from the commandant’s home to the prison barracks where he slept, he smuggled morsels of food to fellow inmates.

After the camp was liberated, Lewkowicz was among the former inmates who found Ludolf disguised as a peasant farmer, causing him to be arrested by Allied troops. He testified against Ludolf and SS Sergeant Otto Striegel when they were tried at Dachau for war crimes, resulting in their executions. Later, he identified Amon Göth, the commandant of Plaszow, whose brutality was graphically depicted in the movie Schindler’s List. Göth used to shoot inmates for target practice from a vantage point overlooking the concentration camp. Touring the camp, Göth would abruptly murder inmates on a whim. He reveled in making Jews quake.

Taken prisoner by the Allies, Göth wore a Wehrmacht uniform rather than that of the hated SS. Lewkowicz was enlisted by the Allies as a Nazi hunter in the wake of Ludolf’s exposure. When he spotted Göth, he lost his composure, “kicking him and punching him in a flurry of rage.” He shouted: “Get up, you bastard, You bastard, damn shit … You will pay for spilling innocent blood. Why did you do it?! You were ready to murder me! … You were a beast, and you are going to pay for it with your life.”

Lewkowicz testified against Göth at the Nuremberg trials. Convicted of war crimes, Göth was hanged at the Montelupich prison in Krakow, not far from Plaszow, the scene of his murderous rages.

The young Holocaust survivor moved on to a job locating 600 Jewish children who had been hidden in monasteries, or placed for their protection with Christian families, and arranged for their reincorporation into the Jewish people and eventual settlement in Israel.

From Europe, Lewkowicz made his way to South America. He was denied a visa to Argentina, unless he listed his religion as “Christian,” which he refused to do. He made his way to a relative there circuitously with stops in Brazil and Paraguay before he could obtain false immigration documents.

He became a diamond merchant in Argentina, traveling throughout Latin America. In Colombia, he met Perla Lederman, and they were married 55 years before her death. They had moved to Montreal, Canada, from which, after Perla’s death, Lewkowicz made Aliyah to Israel as an octogenarian. He died Dec. 26, 2024, at the age of 98.

This is an inspiring book, in which he counsels: “People expect me to be angry at what was taken from us, and them, but anger is like a rocking chair. You keep moving, but it doesn’t take you anywhere. Our job is not to exact revenge, but to repair our communities.”

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.