By Alex Gordon

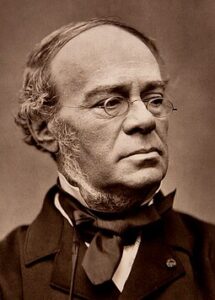

HAIFA, Israel — Jacques-François-Fromental-Élie Halévy was born in Paris on May 27, 1799. He was the son of a cantor and a Hebrew teacher. As a child, he developed a love of music and excelled at playing the violin. At the age of ten he entered the Paris Academy of Music and became a student and protégé of composer Luigi Cherubini, one of the founders and directors of this academy.

In 1819, Fromental won the prestigious Prix de Rome for his composition of the cantata Herminie. As a scholarship student of the French government, he lived in Italy for three years, improving in composition. In 1819 he wrote a work for three-voice choir “De Profundis”, “Out of the Depths” (Psalm 130) with Hebrew text. He wrote six other psalms for performance in Jewish religious services.

From 1827 he worked as concertmaster at the Italian Theater in Paris and taught harmony and later composition at the Paris Academy of Music, of which he became a professor in 1833. Among his pupils were Charles Gounod, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Georges Bizet, who became the husband of his daughter. In 1836, Halévy was elected a member of the prestigious Institut de France and a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Halévy was a popular opera composer who composed at least 36 operas. He died in Nice on March 17, 1862, leaving unfinished his last opera, Noah, based on a biblical story. The score was completed by his pupil and son-in-law Bizet. The premiere took place ten years after Bizet’s death.

Halévy’s seminal work is the opera The Jewess (La Juive), which became one of the cornerstones of the French repertoire for a century. It was a grand opera in five acts, including ballet, choruses, spectacular processions and festivities. The premiere of the opera, based on a libretto by the famous French playwright Eugène Scribe, was a colossal success at the Grand Opera House in Paris on February 23, 1835. One of the admirers of this opera was Richard Wagner, who wrote an enthusiastic review for the German press. The success of the opera was explained by the bright music, strong passions, fascinating intrigue, luxury of staging, love, devotion to religion, showing the Jews’ celebration of the holiday of the Exodus from Egypt Pesach, fanaticism, horror, tragic finale.

The Jewess was for a long time one of the most performed operas in Europe. Only in Paris after the premiere it was played about 600 times. Subsequently, it was used to open opera seasons. Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky wrote that this opera was “hardly the most incisive, if not the best exponent of the traditions and spirit of the French opera school”.

The opera is set in the 15th century in the Swiss city of Constance. Cardinal de Brogni, following the cruel laws, once condemned the two sons of Eleázar, a Jewish jeweler, to be burned. But even in the life of Brogni before his ordination there was a tragedy: his daughter disappeared during a fire in Rome. Meanwhile, rescued by Eleázar, she is brought up under the name of Rachel and knows nothing of her origins. She is in love with Prince Léopold, the emperor’s son, the general who defeated the Hussites, who shows up for a date disguised as a mere mortal, the Jew Samuel. Rachel, learning that her lover is married, denounces him in the presence of the Emperor, the Cardinal and Léopold ‘s wife. The verdict of the court: Rachel and the Prince, who have violated national, religious and class boundaries, and Eleázar with them, must be executed. Conceding to the pleas of the Prince’s wife Eudoxie, Rachel refutes the accusation against Léopold and thus saves him. A terrible death in the fire awaits Rachel and Eleázar. Both of them reject pardon at the cost of renouncing their faith. Rachel is the first to die, followed by Eleázar, who reveals to the Cardinal that he has sent his own daughter to the stake.

Halévy stigmatizes the hatred of Christians against Jews, condemns bigotry and forced conversions to Christianity. However, he does not solidarize with orthodox Judaism either. This position is probably due to the influence of his father. His father Élie Halfon, the son of an orthodox rabbi from Germany, was a Talmudist and cantor, as well as a well-known Hebrew poet. He was secretary-translator of the Paris Jewish community and co-founder of L’Israélite Français, the first Jewish magazine published in France. Élie sought to give his sons, Fromental and Léon, a well-rounded secular and religious education: they attended a traditional cheder. But Élie went against the trend in the Jewish community by sending his sons to a French school rather than a Jewish school. In 1824, he published a book in Hebrew, Lessons in [Jewish] Religion and Ethics, a treatise outlining the foundations of enlightened [Reform] Judaism. Throughout their adult lives, his sons were active in Jewish life. Léon, a professor of French literature at the École Polytechnique in Paris, who converted to Catholicism after his marriage, nevertheless became the first French Jew to write a History of the Jews.

Fromental did not observe the commandments of the Jewish religion. His activities in the Jewish community were more in the spirit of Reform Judaism than orthodox Judaism. At the end of his work, a contemporary musicologist Dr. Karl Leich-Galland (Fromental Halévy – His Life, His Music, 1997), summarizes the composer’s attitude toward his Jewishness: “After sixteen years of marriage, he was very surprised by strict observance of the Jewish Passover in his wife’s family, and in 1859 privately expressed his disagreement with ‘devotees, the pious, the pure’ [customs] of Judaism. But this in no way meant a break with the ‘God of his fathers’ and Jewish Institutions.” In the opera The Jewess, Fromental condemns not only Christian fanaticism, but also Jewish fanaticism, which derives from orthodox Judaism. The main character, after whom the opera is named, turns out not to be Jewish. She is given life,but dies devoted to the faith of her adoptive father, bravely defying the faith of her biological father, a fanatic and murderer.

Many of the composer’s tribesmen, who were not threatened with death, full of fear, parted with the faith of their fathers for the prejudices of the ruling religion. He apparently also condemns the stubborn refusal of the opera’s characters to accept assimilation, a change of religion then common in French Jewish circles, especially in the art world of the time. Despite the tendencies toward revision and assimilation, Halévy did not convert to Christianity and never concealed his Jewish origin or religious affiliation.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the academic college of education, and the author of 10 books.