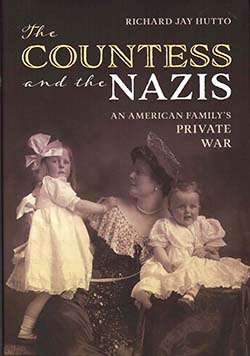

The Countess and the Nazis: An American Family’s Private War by Richard Jay Hutto; Essex, Connecticut: Lyons Press, an imprint of the Glob Pequot Publishing Group, Inc.; © 2025; ISBN 9781493-086566; 220 pages plus acknowledgments, extensive endnotes, and index; $29.95.

SAN DIEGO – U.S. Ambassador Henry White parlayed his and his wife Margaret’s wealth and social prominence into a diplomatic career. It included postings in a number of important European capitals. He was an intimate of President Theodore Roosevelt and was appointed by Woodrow Wilson to help draft a peace treaty ending World War One.

SAN DIEGO – U.S. Ambassador Henry White parlayed his and his wife Margaret’s wealth and social prominence into a diplomatic career. It included postings in a number of important European capitals. He was an intimate of President Theodore Roosevelt and was appointed by Woodrow Wilson to help draft a peace treaty ending World War One.

He and Margaret, who was known by the nickname “Daisy,” had two children. The oldest, Muriel, married German Count Hermann “Manni” Seher-Thiss and thereby became a countess with estates at Rosnochau and Dobrau in Silesia, a region that Germany was required to cede to Poland after World War Two.

Her younger brother John followed their father into the American diplomatic service, also attaining the rank of Ambassador. While John and his wife Betty maintained diplomatic discretion about their negative opinions about the Nazi party, Muriel was outspoken about her low opinion of Adolf Hitler. She thereby became an object of Gestapo suspicion and surveillance.

When the Russian revolution spawned copycat Communist movements in Germany in 1918, Muriel and her daughter Margaret (named for Muriel’s late mother) were caught up in a mob whose members demanded that everyone show their identification before they could pass through blocked streets. She wrote to her brother: “You can imagine how alarming it was to be in the midst of shooting with a child & not be able to get home. Heaven sent me assistance in the person of a young Jew in the Foreign Office who had a pass & who got us through as his wife & daughter.”

Although she was not immune to the antisemitism that was characteristic of socialites at the time, she evolved. Evidence of her change of heart was recorded by Norman Ebbut, a Berlin correspondent for The Times of London, who quoted a portion of a 1937 conversation with a Nazi party official during a dinner in honor of Tom Watson, chairman of IBM:

“Is it true the Party sometimes rewards deserving Jews by making them honorary Aryans?” she asked. When the gauleiter conceded that this happened on occasion, the countess followed up with a line that she must have been mulling for quite some time. “Can you tell me how I could become an honorary Jew?” That kind of bold behavior was hardly typical by then, either for Germans or their American spouses.

In 1939, Muriel was instrumental in the emigration to Australia of Arthur Lederer, a high-society tailor, whose customers included in addition to her, “Hungarian counts, the Knights of Malta, the Prince of Japan, the Maharajah of Jaipur in India, King Farouk of Egypt, the Vatican and the Vanderbilts in America.” As Nazi restrictions on Jews escalated, Lederer contacted his customers in vain seeking an invitation to visit them in their countries. Muriel stepped in and contacted in his behalf Lady Max Muller in Britain, who in turn paid for his family’s passage to Australia and donated 300 British pounds to smooth their arrival in their new country.

The Countess and the Count had three children: the aforementioned Margaret, Hans “Boysie;” and Hermann “Cincie.” Muriel confided to her chef, Albina, her fear that the Gestapo would arrest her and take her to a concentration camp for arranging for her children to immigrate to the U.S. and for showing kindnesses to American POWs, imprisoned near her estate. Albina recalled that Muriel was “afraid to go out to the palace gardens because she claimed that someone was following her.”

The Gestapo demanded that Muriel arrange for her sons to return from the United States (which was then at war with Germany) and to serve in the Nazi army. She stalled.

Muriel also had arranged for Manni, from whom she was then divorced, to escape to his estate in Austria. So, she was the only member of her family remaining at Dobrau when she saw a Gestapo contingent approaching the castle on March 13, 1943.

Muriel ran up to the top floor of the castle’s tower and jumped to her death.

*

Donald H. Harrison is publisher and editor of San Diego Jewish World.