By Judith Kagan

JERUSALEM — A man wearing a long white robe knocks on the door, holding a stick, with the prized afikoman tied up in a handkerchief like a sack slung over his shoulder. The children open the door and ask him, “Where are you from?” He answers, “From Egypt.” Then the children ask, “And where are you going?” The adult replies, “To the Land of Israel.” Then everyone calls out together: “Next year in rebuilt Jerusalem!”

This description isn’t part of a theatrical performance or experiential play, but one of the widespread customs among Libyan and Tunisian Jewish communities. Its role is to provide children at the Passover Seder with a meaningful sensory experience of the most formative collective memory of the Jewish people—the Exodus from Egypt, the journey from slavery to freedom.

The Game Precedes the World

Those who perceive play as something reserved for children might be surprised by the playful elements that have entered our holiday customs through the back door. But one can certainly argue that re-enacting the Exodus is not (only) a children’s activity. Play serves an essential and meaningful role in how humans perceive, learn about, and experience the world.

Human beings have engaged in play since ancient times. In Babylon and ancient Egypt, religious priests dramatized the stories of the gods, and during the Middle Ages, community theater was an integral part of communal life, dramatizing biblical narratives. In the 1930s, with the emergence of psychology, psychodrama was introduced, turning play into a therapeutic tool.

Many scholars have explored play as a method for learning, identity formation, and understanding others, one of whom is Johan Huizinga. In his book Homo Ludens, Huizinga argues that play preceded culture itself. Before humanity had written laws, science, or art, people engaged in competitive games, rituals, and imagination. According to Huizinga, it is from this “playful space” that some of the most central institutions in our lives emerged. For instance, the legal system grew out of disputes in competitions and games, religious rituals are full of playful and symbolic elements, and even wars have retained patterns of behavior and competition resembling games.

Huizinga coined the concept of the “magic circle”—referring to the space, timeframe, and location in which the game takes place, governed by special rules that participants voluntarily accept. Within this magical circle, Huizinga notes, a unique experience of freedom and order simultaneously emerges: people can experiment with behaviors without real-world consequences, while at the same time the game shapes, “educates,” and serves as a microcosm of society. In other words, Huizinga sees play not merely as amusement, but as a way for cultures to create meaning, form identities, and preserve values.

Scallions and a Beginner’s Guide to Wandering

With the rise of fantasy and science fiction fandom in the mid-20th century came new ways of imagining and playing. Role-playing games became a defining part of “geek culture.” Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) began as a tabletop game in which players step into fantastical roles and set off on collective adventures. Players invent characters, shape their personalities and traits, craft unique voices or catchphrases, and act them out. The game went on to inspire countless video games—many of their creators were once kids playing D&D.

LARP (Live-Action Role Playing), in contrast to tabletop gaming, involves full-body immersion. Players wear costumes, move, speak, and act within a narrative world. Some liken it to improvisational theater: each participant has a role and goals, and while there may be a central plot, it’s the players’ decisions that drive the story forward.

Anyone straddling Jewish tradition and pop culture can’t help but notice the striking parallels between LARP and the rituals of the Passover Seder.

The resemblance starts with a well-known line from the Mishnah (Pesachim 10:5): “In every generation, a person is obligated to see himself as if he had come out of Egypt, as it is said: ‘And you shall tell your child on that day, saying: It is because of what the Lord did for me when I went out of Egypt’” (Exodus 13:8).

Maimonides (the Rambam) offers a slightly different, but significant formulation: “In every generation, a person is obligated to show himself as if he had come out of Egypt.”

“To show himself,” as opposed to “to see himself,” shifts the emphasis from inner reflection to outward expression. Maimonides highlights the act of performance and exaggeration. The Seder, in this light, is not just a moment of internal contemplation, but a deliberate reenactment—an active identification with the journey from slavery to freedom.

This intention to foster deep identification—combined with the commandment to “tell your child on that day”—gave rise to a wealth of playful customs across Jewish communities. These practices serve not only to keep children awake and engaged but to draw everyone into a shared, theatrical, emotionally resonant experience.

Take, for example, the Libyan and Tunisian custom described above, where the Exodus is physically acted out. Among Persian Jews, it’s customary to whip one another with long green onions during the song Dayenu, symbolizing the lashes of the Egyptian taskmasters. And let’s be honest—what kid could possibly fall asleep with the promise of a full-blown onion fight with their siblings?

The Seder Leader as Dungeon Master

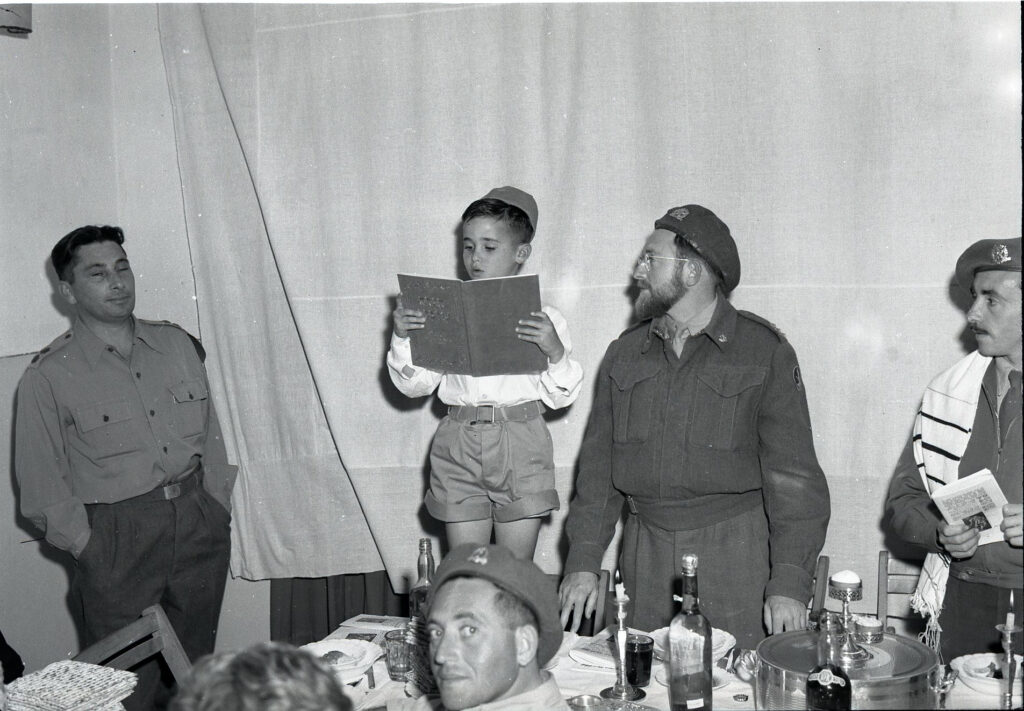

Game-like elements are embedded even in the core sections of the Passover Seder. The story is already known, and roles at the table emerge naturally: adults become guides and narrators, while children are the seekers and questioners. The Seder leader plays the part of a Dungeon Master, steering the participants through the unfolding tale of the Haggadah.

In fact, the Haggadah feels almost tailor-made for this Jewish version of live-action roleplay. It’s both a narrative script and an instruction manual. It includes dialogue—like the Four Questions, which place a spotlight on the youngest child and show that even the smallest participant has a vital role. The Haggadah leads the group step by step, like a screenplay. Along the way we meet symbolic characters: the Four Children, Pharaoh, and of course, the most mysterious of them all—Elijah the Prophet. Throughout the text, each participant is asked to make the story their own: “It is because of what the Lord did for me when I went out of Egypt.” Each person becomes the central figure in the drama of redemption.

The Seder table itself is rich with props and symbols—matzah (the bread of affliction), maror (the bitterness of slavery), charoset (mortar and bricks), and the Four Cups (redemption). Each is a sensory cue, drawing us deeper into the Exodus experience.

One especially playful element is the theft of the afikoman. Children “steal” a piece of matzah, and the adults must bargain to retrieve it in order to conclude the Seder. It’s the Seder’s equivalent of a side quest. Surprisingly, the tradition is ancient: the Sages even said, “the Matzot are snatched at the Seder so that the children will stay awake.” In other words, there was a conscious choice to inject play into the evening—to keep the youngest engaged and involved.

Finally, after the meal and the Four Cups, many of the Haggadah’s songs—Dayenu, Chad Gadya, and others—are essentially group games, performed with hand gestures and theatrical energy. In Chad Gadya, for instance, families often take turns giving voice to the various characters—the cat, the dog, the goat—in a playful vocal performance that brings the night to a joyous close.

These elements are not just there for fun. They’re designed to awaken all the senses, to make the story come alive. The Seder invites us to become Israelites, learning not through lectures but through lived experience. We act like newly freed people, we sit back and recline, we eat their food, speak their words. It is, at heart, both a religious and educational journey—because people internalize values and stories best when they live them in the first person.

A Glimpse of a Different Life

While the Seder may be the most overtly game-like holiday ritual, it’s far from alone. Other Jewish traditions hold playful, even LARP-like qualities—sometimes hidden in plain sight.

One such ritual occurs on the holiest day of the year: Yom Kippur. During the Musaf prayer, great attention is paid to the Seder Ha’Avodah, a detailed reenactment of the High Priest’s service in the Temple. In many synagogues, this isn’t merely read aloud; it’s delivered as a vivid narrative that invites the entire community to feel part of something ancient and hoped-for—a ritual not just remembered, but longed for in future.

Surprisingly, another ritual steeped in live-action symbolism happens every week: Shabbat.

Shabbat is sometimes described as “a taste of the World to Come”—a phrase that highlights its role as a momentary window into an ideal future. When Shabbat begins, we step out of our weekday reality and into its “magic circle.” It is an alternate world with its own rules, symbols, costumes (Shabbat clothing), strict rules and restrictions (the 39 Melachot), and shared story: a vision of a perfected world with no competition, no worry—where everything is already prepared.

This weekly game is not escapism. It offers a taste of an alternative way of life—one of presence, rest, community, and meaning. Shabbat isn’t just a ritual—it’s an act of immersion, of entering character, of stepping into another universe. And like any good LARP, we know the framework is temporary—but we also know it’s meant to change us when we return to real life. It’s a rehearsal for redemption, a glimpse of the ideal, a living game that holds the hope that one day—we won’t just play it. We’ll live it.

*

Special thanks to Daniel Fidelman for his assistance in writing this article. This article originally appeared in The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.