By Alex Gordon

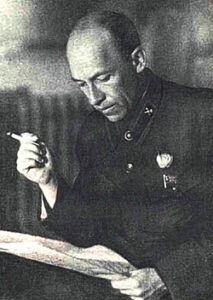

HAIFA, Israel — Isaak Dunayevsky, the USSR’s most famous and highly paid pop composer, twice winner of the Stalin Prize, was the most talented and most influential composer of his genre in the Land of the Soviets.

Dunayevsky was born on January 30, 1900, in the Ukrainian village of Lokhvitsa into a Jewish family. His father served in a bank and had a small business producing fruit water. His mother was a deeply religious woman and actively attended synagogue. She had a good ear and loved to muse on the piano. At the age of four, Isaac was picking up by ear on the piano tunes he heard in the town garden. At the age of six he could separate a melody in two voices, in fiddle and bass clefs, and at the age of ten he composed his first songs. There were seven children in the family, five of whom became musicians.

In 1910, Isaac entered the music school in Kharkov in the violin class. At the same time, he studied at the gymnasium, which he graduated with a gold medal. After graduating from the conservatory as a violinist in 1919, he began working at the Kharkov Drama Theater, headed by Nikolai Sinelnikov, where he was first a concert violinist, then conductor and head of the musical part of the theater. He made his debut there as a theater composer, composing music for new plays.

In 1924, Dunayevsky moved to Moscow, where he became musical director of the Hermitage Theater, and from 1926 he became head of the musical section of the Theater of Satire and the Moscow Operetta Theater. In 1929 he moved to Leningrad, where in 1929-1934 he was musical director and chief conductor of the Leningrad Music Hall.

Dunayevsky became one of the founders of Soviet operetta and musical movie comedy. The composer made music one of the main components of the dramaturgy of motion pictures. Together with film director Grigory Alexandrov and poet Vasily Lebedev-Kumach the movie Merry Boys (1934) brought the composer wide fame. From 1934 to 1940 he composed music for 16 films and 13 operettas. Thanks to the performance of his songs in movies, Dunayevsky became the most popular Soviet composer, a classic of Soviet song. His beautiful and cheerful songs were a great success. In 1936, he wrote the patriotic “Song about the Motherland,” heard in the movie Circus, which has the following words:

Wide is my Motherland,

Of her many forests, fields, and rivers!

I know of no other country

Where a man can breathe so freely.

From Moscow to the borders,

From southern peaks to northern seas,

As the master a man stands

In his wide Motherland.

The English composer Alan Bush, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain since 1935 (Dunayevsky was not a member of the Communist Party of the USSR), placed a note “Creator of a Great Song” in a collection dedicated to Dunayevsky’s memory, where he writes that “Song about the Motherland” is “one of the greatest songs ever created” and that Dunayevsky “enriched mankind” with it.

Dunayevsky was a cheerful romantic and skillfully harmonized disharmony. Dostoevsky’s gloomy and suffering Russia was transformed into Dunayevsky’s bright and happy Russia. The writer’s Russia was the truth, the composer’s Russia was a talented painted picture. In the country in which this song was born, in the year of its creation (1936), “enemies of the people” were being tried and executed.

Contrary to what is said in the song, a man in that country did not breathe freely. He was not the master of his homeland, just like the composer himself. With his lyrical and patriotic songs, Dunayevsky created a fairy-tale country that had nothing in common with the real Soviet Union. Before him, utopias were written on paper. Dunayevsky, with the help of poet Vasily Lebedev-Kumach, drew a beautiful musical utopia country.

The beautiful melodies of Dunayevsky’s musical utopia spread throughout the “wide country,” flew to all its corners, and carried on their warm waves the joy of people who were hounded and bored, who were intimidated and lived meagerly, who were afraid of reality and enjoyed the cheerful melodies. Dunayevsky’s music created a parallel virtual world, spraying fireworks of optimism and springs of confidence in today and tomorrow. The song helped Soviet people to live the illusions they needed.

Jews especially needed illusions, for they needed to survive in an atmosphere of second-classness. They were in dire need of a beautiful, melodic, optimistic sound, for their lives of stepchildren were disharmonious. The beautiful melodies of the Jewish composer penetrated into the souls of the disharmoniously existing Soviet citizens who needed the musical beauty of mass songs to save them from the heaviness of queues, from the boredom of party and trade union meetings, from May Day and October demonstrations, from difficult everyday life, from low wages, from the gray monotony of hard everyday life, from the shortage of food and goods, and pushed the citizens of “the country of heroes, the country of dreamers, the country of scientists” (words from Dunayevsky’s song from the movie The Bright Path) to excessive, unnatural joy.

There was a need for a way out of the unsettled, unsecured, complicated, monotonous, ugly, “socialist” life into a beautiful world of soulful, lyrical and patriotic motifs. The ugly reality was to be compensated by a beautiful, heartfelt, universally accessible, joyful, mass song, a “bright path.” Life under socialism was stuffed with obligatory optimism. It was a masquerade ball at which hopelessly tired and sad faces were hidden under laughing masks.

The Jewish theme did not remain only in Dunayevsky’s childhood. In January 2001, the Chairman of the USSR Composers Union Tikhon Khrennikov gave an interview in which he recalled: “Here, for example, ‘My native country is wide.’ It was written by a Jewish composer, but it is entirely Russian music. Dunayevsky wrote Jewish music for some movie, there was a Jewish wedding. He wrote it specially.”

Most likely Khrennikov was referring to the movie Seekers of Happiness (1936) about Jewish settlers in Birobidzhan, in which there is a wedding.

In 1949, during the anti-Jewish campaign of the “rootless cosmopolitans”, the composer was harassed. They wrote about his operetta Free Wind: “The Soviet man is not felt in it, but there is a noticeable attempt to squeeze the thoughts and feelings of our contemporary into Western, alien plots.”

His longtime partner in creating musical movie masterpieces, director Grigory Alexandrov, refused to cooperate with the composer. His 50th birthday in 1950 was ignored by the authorities. In 1953, the antisemitic “case of poisoning doctors” broke out. The composer’s cousin Lev Dunayevsky, a urology professor, was arrested. The composer refused to condemn him and did not sign the letter against the “poisoning Jews.”

Isaak Dunayevsky died of a heart spasm in Moscow on July 25, 1955.

*

Alex Gordon is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education, and the author of 11 books.