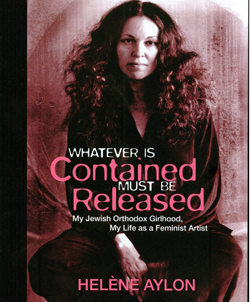

Whatever is Contained Must Be Released: My Jewish Orthodox Girlhood My Life as a Feminist Artist by Helène Aylon, Feminist Press, New York, 2012, ISBN 978-1-55861768-1, 287 pages, $29.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO–The author of Whatever Is Contained Must Be Released is a conceptual artist for whom Torah–and the rejection of some of its passages–have both informed her work and made it controversial. At one stage in her career, Helène Aylon poured gallons of paint on a canvas lying face-up on the floor. Then, after the top layer dried, she stood the canvas up, and the contents inside would burst through the thin upper bubble-like layer and create their own pattern as they flowed by gravity down the canvas.

SAN DIEGO–The author of Whatever Is Contained Must Be Released is a conceptual artist for whom Torah–and the rejection of some of its passages–have both informed her work and made it controversial. At one stage in her career, Helène Aylon poured gallons of paint on a canvas lying face-up on the floor. Then, after the top layer dried, she stood the canvas up, and the contents inside would burst through the thin upper bubble-like layer and create their own pattern as they flowed by gravity down the canvas.

All of this was a metaphor for the artist’s own life, in which as a girl in a frum family she was kept in a bubble that could not contain her after her husband–a young rabbi–died at an early age from cancer, leaving her alone with two children.

Woven through the autobiography are photographs of the artist’s works along with poems about her growing sense of exclusion from Judaism. She takes umbrage “that priests who sprinkle the blood of slaughtered animals in the Temple must forbid a woman who is bleeding to appear before the Lord.” She writes how as a schoolgirl she unsuccessfully sought a woman’s point of view in the Jewish texts, but instead found misogynistic passages such as one blaming rape victims for their loss of virginity. She imagined Jewish foremothers lamenting that “we are banished as was Hagar in the wilderness… loathed as was Lea in her darkened bed chamber … we are being used as was Sara, handed over….we are blamed as was Chava, the first….”

Describing her arranged marriage while still a teenager to an Orthodox rabbi, who announced at their wedding that no one else was permitted to dance with her, the author continues to build her indictment of Orthodox Judaism, commenting that it certainly was not a woman who decided that menstruation rendered a woman “unclean” like a leper or a corpse, nor was it a woman who designed the ketuba in which the names of the bride’s and groom’s mothers are not even mentioned, nor was it a woman who worded gravestones which identify the deceased father but not his mother.

Art rescued the widowed rebbetzin, giving her a creative channel for her anger as well as introduction to a world of different ideas. She continuously re-invented herself, including the taking of the surname Aylon, which is a Hebraicized version of her first name Helène. She took a lover, who turned out to be drug addict, and left him behind when she moved from New York City to Berkeley, where she began perfecting her Paintings That Change, in which “I painted from behind the surface of the paper, allowing the oils to seep through naturally in their own time, outside of my doing. I would wait for the image to manifest on the front surface through chance-absorption-and I would accept the outcome.”

She became involved in the anti-war movement, gathering sand and dirt from U.S. military and nuclear sites, storing them in an “earth ambulance” and eventually incorporating them into an installation outside the United Nations Building in New York. Apparently San Francisco State University didn’t get her work, she was denied tenure as an art professor. In another of her projects, sand and earth were scooped up in atom-bombed Japan, and sent floating with poems down a river. And she moved back to New York City.

When her son Nathaniel, who had been sent to yeshiva, was to be married to Tobe, Aylon wanted to include the names of their mothers on the ketuba–a request that might have torpedoed her son’s Orthodox wedding had there not been a compromise. While Aylon was refused permission to put the mothers’ names in the ketuba, she was allowed to insert asterisks, indicating a footnote — or in this case a note on the reverse side of the document.

The idea of editing texts germinated thereafter, and Aylon set upon a major art task. She took a Hebrew Bible and put a thin coat of clear pinkish plastic over each word that she imagined was written not by God but by Moses or some other man. These were words that she imagined a God who loves all people equally could never have uttered. These words demeaned women, or justified violence, such as “smite.” It took six years to complete this feminist version of the 54-chapter Bible in a project she called “The Liberation of God.”

Her mother, Etta Greenfield, in a written comment at the Jewish Museum about “The Liberation of God” when it was shown there, said “There are good teachings in the Torah. Why are they not acknowledged in your piece? I would have felt better if you did mention the greatness of the teachings.”

It is said that one of the religious duties of a Jew is to question God. Aylon demanded answers to why God had allowed men to become usurpers of the Divine. But in questioning Judaism, and at times expressing the feeling that there was no room for her in it, she never abandoned it.

Why not ?

That simply wasn’t possible, given Aylon’s great admiration for, and inspiration derived from, her mother’s loving, trusting, gentle, giving, and Torah-inspired ways.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com