By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — Rabbi Stanley Rabinowitz, who helped comfort President Lyndon B. Johnson and the nation after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, died in his sleep Friday, June 8, in the nursing facility of Seacrest Village Retirement Community in Encinitas

Rabinowitz, 95, longtime rabbi of Adas Israel Hebrew Congregation in Washington, D.C., had moved to San Diego in his later years to be near his daughter, Dr. Sharon Chard-Yaron. She survives him as do another daughter Judith Argaman of Herzliya, Israel, four grandchildren and one great-grandson. Funeral services will be held at 11 a.m., Friday, June 15, in the congregation in Washington D.C. that he had led for 26 years, with burial to follow at Adas Israel Cemetery.

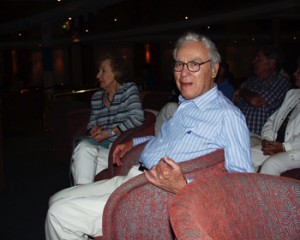

In 2001, I had the opportunity to interview Rabbi Rabinowitz when we met aboard a cruise ship. In that interview which first appeared in the San Diego Jewish Press-Heritage, he recounted some of the memorable episodes of his life. That interview follows:

*

ABOARD MV OLYMPIC EXPLORER (special) — I sat down to chat with my fellow passenger, Stanley Rabinowitz, who I had learned was a retired Conservative rabbi. It was a day at sea, and we both had plenty of time; he, to reminisce, and me, to prompt him occasionally to tell yet another story about some of the interesting people he knew. His had been no ordinary career: he had preached a healing sermon to President Lyndon B. Johnson a few days after President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Another martyred leader, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, once had been a member of his congregation–and taught the members of Adas Israel Hebrew Congregation a very valuable lesson about biblical Hebrew. While the people in the congregation were Jews like you and me, some of them were also very famous: Rabinowitz performed a marriage for former Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Abraham Ribicoff, and buried former U.S. Supreme Court Justice and U.N. Ambassador Arthur Goldberg, his dear friend.

The rabbi also once was asked to quickly round up about 30 kippot and pamphlets with the transliterated prayer for grace after meals. President Carter was at Camp David negotiating peace between the Egyptians and the Israelis, and decided it would be great to have a ceremonial Shabbat meal. Not having the necessary accoutrements on hand, the Israelis telephoned Rabinowitz with an SOS.

Yes, Rabinowitz had an unusual career. He had served as the national president of the Rabbinical Assembly, and as the Washington chairman of the American-Israel Public Affairs Committee when that organization was in its infancy. For 26 years until his retirement in 1986, he had served as rabbi of Adas Israel. Put in terms Washington D.C. residents could readily understand, he had served during the presidencies of Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Baines Johnson, Richard M. Nixon, Gerald R. Ford, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

Occasionally watching the far off sea horizon roll as our ship sliced through the Caribbean, I asked the rabbi what special memories he had, if any, about each of those presidents. None about Eisenhower, Rabinowitz confessed. He had arrived at Adas Israel in 1960, the last year of Ike’s term, after serving as rabbi for seven years in Minneapolis, and before that, for another seven years in New Haven, Conn.

He became active in Washington’s interfaith movement and it was his turn during his fourth year at Adas Israel to deliver a Thanksgiving sermon — at the large Presbyterian Church. It was Thanksgiving, 1963, just a few days after President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. The nation was in deep mourning and the new President, Lyndon Baines Johnson, was among the worshipers at the church that day.

“I took the theme from Rabbi Akiba that just as we give thanks to God for the blessings, so must we give thanks to God for the evil–because out of evil you can extract a blessing,” Rabinowitz recalled. “That was the essence of the sermon and it struck Johnson very well. He felt it was appropriate to the moment: out of the evil, he would extract a blessing.”

Shortly afterwards, Rabinowitz received a telephone call from the new First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, who asked if he could please bring a copy of the sermon to the Johnsons’ private residence. The Johnsons had not yet moved into the White House, which Jacqueline Kennedy and her children were in the process of vacating. The rabbi replied that he didn’t have a copy of the speech, because he had spoken from notes, but would type his notes if she so desired. She said she would be most grateful, and thanked him.

So he typed the speech, and delivered it to the Johnson home, where it was accepted by their daughter, Linda (who later married Chuck Robb). Shortly afterwards, Rabinowitz made a trip to India, where the U.S. ambassador handed him some State Department papers that included the text of the speech that President Johnson had made at the dedication of a synagogue in Austin, Tex. Johnson had quoted Rabinowitz’s Thanksgiving Day address.

Was he nervous delivering a sermon to the President of the United States, especially during such a traumatic time in our nation’s history.

“Yes,” the rabbi agreed. “I believe I was.”

One of the momentous events occurring during Johnson’s administration was the outbreak of the Six Day War in June of 1967 between Israel and its Arab neighbors. One of the members of the synagogue, Sheldon Cohen, the director of the Internal Revenue Service, “was terribly upset,” Rabinowitz recalled. “He went to see Johnson and said ‘you just can’t let this happen to Israel’ and Johnson wrote him a letter in which he reassured Cohen that no matter what the crisis would be, the United States would stand there and make sure that Israel didn’t fall. It was very reassuring, because the public posture of the United States toward Israel was terrible.”

When one thinks of the Johnson Administration, one also remembers the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy. The turbulent politics of the 1960s “split the congregation,” Rabinowitz said.

“There were those who were very much against the War in Vietnam and the majority of course said ‘don’t rock the boat.'” he recalled. “We were split so badly that a goodly number of people resigned from the congregation saying that we were not activist enough.”

Rabinowitz remembers one anti-Vietnam War march in which Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel participated. When word circulated that Heschel was planning to take such a public position, “the Israeli embassy was very upset about it because the embassy felt that what happened in Vietnam would happen in Israel,” Rabinowitz said. “If America wouldn’t come to the aid of Vietnam, they wouldn’t come to the aid of Israel. They saw a parallel. They saw themselves as being the victims, just like the South Vietnamese. They asked me to intercede with Heschel and to ask him not to march. I wrote to him a pleading letter but I never mailed it. I felt I didn’t have the right to, even though I felt what he was doing was wrong. It was a very painful time in American life.”

Riots erupted in Washington after the assassination of Martin Luther King, sparking a debate at Adas Israel whether to move the synagogue from the city’ predominantly African-American population.

“”The riot hit Jewish businesses especially hard, and many people left the city and went to the suburbs and they wanted to move the synagogue to the suburbs too,” Rabinowitz said. “But they couldn’t find a place that would be satisfactory, so they decided to be inconvenient to everybody, and to stay. And it is good that they stayed, because where we are now, there is a metro stop, a subway, and the synagogue is thriving beyond anything I would have imagined in our day.”

Rabinowitz, horrified by the violence, was among those who wanted to pull out of Washington D.C. “I’m afraid I favored the move, but then on reconsideration, I said ‘well, maybe the synagogue is too new to be rejected.’ It was built in 1950.”

Most ambassadors of Israel were members of Adas Israel during their tenure in Washington, and that included future Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who came after the Six Day War and served during the Nixon administration.

“He was unaccustomed to synagogues,” Rabinowitz recalled. “He had to come on formal occasions and when he came, he read the Torah. He wouldn’t make a good ba’al koreh (Torah reader), because he didn’t chant it, but he did read it aloud. Once when he was reading it, he stopped and said: ‘Hey, there is a mistake here!’ and there was a mistake; they (the scribes) had left a vav out. He embarrassed our ba’al koreh who had used the same Torah for 20 years and had never seen the mistake. Rabin, the first time he gets up, spots it and stops. It was a minor thing, but of course, we had to bring another Torah.”

When Rabin left the United States to return to Israel, “he made a farewell address to the congregation, which is something I will never forget,” the rabbi said. “He said ‘I was born a Jew and I am practiced being a Jew–it was a matter of birth. In the United States, in this congregation, I learned a very different way of being a Jew, and it has stretched my life.’ It was very touching because I knew that he meant it. His child–Yuval–was bar mitzvahed at our synagogue. He (Rabin) was a very spiritual person, this military guy who never got near a synagogue before.”

Among Jewish appointees in the Nixon Administration were Commerce Secretary Phil Klutznick, whom Rabinowitz had known in B’nai B’rith Movement, and National Security Advisor–later Secretary of State– Henry Kissinger. Klutznick was a member of the congregation; Kissinger was not, although he and Rabinowitz crossed paths occasionally.

One year, Kissinger was invited to the bar mitzvah of the son of Simcha Dinitz, who succeeded Rabin as an Israeli ambassador to the United States. “I was told that he was coming, but he didn’t show up because of a crisis. However, I saw Kisssinger that night at an Israeli embassy reception, and I told him: ‘Mr. Secretary, I had two sermons prepared: one in case you were there; one in case you weren’t.’ He said quickly, ‘I am sure you delivered the better one.’ He was well-known for his quick repartee.'”

When the campaign among Russian Jews for permission to emigrate to the West gathered steam, the Soviet Union sent a delegation of Jews who were loyal Communists to Washington. A member of his congregation prevailed on Rabinowitz to entertain these anti-Refusenik Jews, even though the Israeli Embassy urged him not to.

“We had them for dinner, and served Chicken Kiev, but we also had several knowledgeable people who could challenge them, including the late Congressman Sidney Yates, Rabbi Richard Hirsch (Reform) and his Russian born wife, and David Korn, an anti-Russian activist,” Rabinowitz said. “Those guys (the visiting Russians) were happy to leave our home unscathed. They thought they scored points, but they didn’t.”

Rabinowitz said the group was led by a man who obviously was a KGB agent named Gidany Fodosov. Subsequently, “he kept peppering me with gifts of vodka and kept inviting me to lunch to ask me all sorts of questions about America,” the rabbi said. “I had to be very cautious. When Nixon resigned and Ford became the President, Fodosov called me up, and asked, ‘Does this mean that Ford Motors is going to take over the country?’ That is how dumb they were about America; I couldn’t convince him that there was no connection.”

The rabbi believes his first invitation to a formal social function at the White House came during the Ford Administration. “I don’t remember the reason for it, perhaps it was for Yitzhak Rabin, but I got to dance with Betty Ford.”

Next came the Carter Administration and Camp David. Besides rounding up skullcaps and copies of the birkat hamazon for the negotiators’ dinner at Camp David, Rabinowitz said he vividly remembers the ceremonies attendant to the signing of the Camp David accords by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat.

“There was a big service at the Lincoln Memorial before the Camp David signing,” he said. “President Carter’s sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, gave a sermon and I gave an invocation. Then we went to a great big tent, where we had dinner, which was kosher, and it was something to behold.” The three-way handshake among Begin, Sadat and Carter was “thrilling, just thrilling–a high point.”

Sadat subsequently invited Rabinowitz to visit him in Egypt, which he did. “I went with a delegation and went to his house. Someone asked him, ‘can’t you leave even a portion of the Sinai for Israel?’ and he said, ‘this is my land and I want every inch back.’ And he was very candid. He wasn’t making peace with Israel and he wasn’t making war with Israel. He noted that there were a few million Jews in Israel compared to 60 million Arabs, and if Arabs just left the Jews alone ‘eventually we will absorb them. Let’s have peace. We can take over Palestine easier with peace than we can with war.'”

Like Rabinowitz, President Ronald Reagan had grown up in Iowa, where as a radio broadcaster he used to narrate the action for major league baseball games by embellishing on the results that came over the play by play wire. Although they met, and Reagan sent a formal letter of congratulations to Rabinowitz when the rabbi retired in 1986, there were no real personal contacts.

Even though politics is to Washington as entertainment news is to Hollywood, much of what Rabinowitz did during his tenure had little to do with the nation’s governance. He’d preach sermons on Friday nights, and would preside over the Torah reading on Saturday mornings– just as rabbis do all over the country. During his tenure, the congregation had approximately 1,200 families; since his retirement it has grown to about 1,800 families. While he was the rabbi, the biggest crowds came on Friday nights; less than 500 was a disappointment. Today, the bigger crowds come on Saturdays to hear the Torah read, among them: Congressman Henry Waxman of Los Angeles.

Rabinowitz and his wife, Anita, have two daughters: Judith Argaman lives with her husband and three children in Jerusalem. Sharon Chard-Yaron and her husband reside in the University City area of San Diego.

As emeritus rabbi at Adas Israel, Rabinowitz still preaches an occasional sermon or delivers a lecture, and remains quite interested in world affairs. “I had dinner with (Yasser) Arafat no more than a year ago,” he said. “A Shabbas dinner no less. A member of the congregation–Esther Coopersmith–invited me; she thought it would be a nice thing for him to see how Jews celebrate the Sabbath. So she invited him to dinner and invited me to make kiddush.”

Rabinowitz recalled telling Arafat: “You know, we are cousins. We can trace our ancestry back to the same ancestor. Our paths have veered, separated, sometimes in conflict, but I pray that the day will come when we shall someday be able to resume our relationship in peace and friendship..”

Arafat responded, “Yes, in friendship.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com