-Fourth in a Series–

Photos and story by Donald H. Harrison

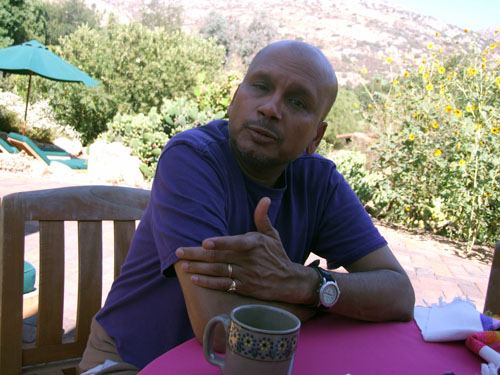

TECATE, Mexico — Out by one of the swimming pools, he was eating a quesadilla while I was enjoying a vegetable-packed omelet with salsa, both typical foods of this region. However, the food that chef Rhagavan Iyer and I were talking about was matzo ball soup — the way the way he experienced it in India. It was a fairly typical encounter at Rancho La Puerta, which enjoys a globe-trotting clientele.

Iyer, a master chef and cookbook author, was at the ranch to teach the guests a little bit about Indian cooking. One of his three published cookbooks is titled 660 Curries but don’t get the idea he is talking about that yellowish powder that you shake from a can. He wrinkles his nose at the very thought of it. In his native India, he said, “curry” means “sauce,” and there is an endless variety. He said none of the 660 dishes he describes in the book — including matzo ball soup — taste anything like what Americans call “curry powder.”

Matzo ball soup? Over the millennia, India had three waves of Jewish immigration. The Bene Israel, who live around Iyer’s native Bombay (or Mumbai, as some call it), the Cochini Jews, who live on the Malabar Coast of southwest India, and the Sephardim.

The self-identifying Jews of Cochin may have diminished in number to perhaps less than a minyan, but Iyer remembers once meeting a Mrs. Cohen there who made yarmulkes by hand, and visiting a 14th century Jewish cemetery right across the street from a 18th century synagogue. The Cochini Jews came to India in search of spices to export to Europe, and they built businesses, became influenced by the local culture, intermarried, and stayed. The area in Cochin where they lived still is called “Jew Town,” without any malice.

“They would cook in traditional ways where they would incorporate and maintain their dietary restrictions and lifestyle and then incorporate what was available locally,” said Iyer.

I found myself fantasizing that Iyer’s matzo ball soup recipe was the result of a centuries-long process of acculturation, assimilation, and development of a synergistic cuisine.

He laughed an infectious laugh which, after a day or so, guests anywhere on the health ranch could recognize. It turned out the recipe was of far more recent vintage — created in concert with an internist friend from Minneapolis, Dr. Jeff Mandel, who had accompanied him on a recent trip to India.

Over the years, Mandel had introduced Iyer to Jewish foods, so the chef knows that among matzo balls, there are “dunkers” and “floaters.” Having been a regular at the Mandels’ Passover seders, he knows, too, that matzo also serves as the “afikomen” or dessert, for which children ceremoniously go searching.

Mandel and Iyer created the matzo ball soup blending the matzo balls “with some of the more perfumed spices” which are used by cooks in Cochin.

Iyer graciously agreed to share the recipe with San Diego Jewish World readers, and it is printed at the bottom of this article.

In researching 660 Curries, as well as a previous book, The Turmeric Trail, Iyer went to villages and towns, sampling food, visiting kitchens and asking lots of questions.

“To me,” he explained, “food is a wonder of culture. People open up, and that is when you can relate to somebody. I would go up to total strangers all the time because they like to share, tell their stories. It is story-telling that bridges cultures.”

It helped that Iyer speaks four languages of India, and also that he loves to sample “street foods.”

“They are very reflective of what people normally like to eat,” he said. “They’re a poor man’s source of food that you can grab and go. The more you start talking to the vendors, you get to know a little more.”

He said he typically asked the vendors what kind of food they were making, what was in it, how do you make it — “and that is how the conversation starts. The women especially find it very funny in a way, ‘here is a man who is interested in my territory.’ There is an apprehension at first, but once they realize that I know what I am talking about in terms of food, they really open up.”

Iyer related that the vendors soon learned that “I know what this is or what that is, and when I ask leading questions, there is a pleasant surprise on their side — ‘Oh, you know what you are talking about!’ I love that, it’s the fun side of working on a book.”

Sometimes, Iyer would be invited into homes, and whereas most of the men would be outside discussing what they considered to be important affairs, Iyer liked to follow the women of India into the kitchen to see exactly what they were doing.

India is a large country with many regional cuisines. There is no one taste. He remembered he once lectured on an avocado dish and a man from India came up to him and said avocados were not an Indian food/ Really? asked Iyer. Hadn’t the man ever visited the State of Kerala in southwest India? Avocado trees abound near the coast.

A day after we had breakfast together, I visited the place Rancho La Puerta has named La Cocina Que Canta, the Kitchen That Sings, to watch Iyer teach about Indian cooking. Approximately 15 guests were divided into teams of two or three, and assigned different dishes to prepare. Following his recipes, they collaborated on a six-part meal.

The menu, pareve and dairy, included Sabudana vada (tapioca fritters with a coconut-sesame seed sauce); sprouted bean salad with potato croutons; Paneer Jalfrezie (creamy cheese with red onion and bell peppers); avocado pomegranate relish; Palak Suva (spinach with fresh dill) and cranberry mango compote. I can testify that absolutely none of these dishes tasted anything like what we in the United States have come to think of as a “curry.”

Before the meal started, the guests led by Rancho La Puerta’s sous-chef, Gabriela Lopez Alvarez, went outside the kitchen to the 6-acre Tres Estrellas (Three Stars) organic garden to pick some ingredients for the varied menu. Cherry tomatoes were among the freshly picked produce that we hauled in — the flavor so much better than that of store-bought tomatoes which have to ripen in trucks and on shelves.

I monitored vegans Priscilla Feral and Bob Orabona of Norwalk, Connecticut, as they carefully followed Iyer’s directions for making tapioca fritters with the coconut-sesame seed sauce– a recipe that also included some of those just-picked tomatoes.

The recipe involved soaking and squishing the tapioca pearls, grinding peanuts in a food processor, and adding to them cilantro, chilis, garlic and ginger; kneading all this with potatoes and salt into balls roughly 2 1/2 inches in diameter, and frying the fritters. Making the sauce, meanwhile, involved frying coconut and sesame seeds in vegetable oil and adding to this a blend of cilantro leaves, coarsely chopped tomatoes, and green Thai, cayenne or serrano chilis. Finally, directed Iyer, “place two fritters on each individual serving plate and cover them with the spicy sauce. You will marvel at the fritter’s crispy exterior and the soft, zesty, gooey interior.”

For fans of Israeli falafel, he added, there’s another fun way to eat the fritters: put them inside some pita bread for a different type taste sensation.

Feral is president of the international Friends of Animals organization, and Orabona is its operations director. After they prepared the fritters, they put the experience into their context.

“I think a plant-based diet is good for the world and it is good for us,” Feral said. “It eliminates the idea that we have to breed animals into existence and then try to mitigate the harm that we cause them in the process of ultimately consuming them. So I choose to opt out as a humanitarian and as someone who is lucky enough to live in a world, a country, with a lot of alternatives to meat-based, omnivorous diets.

“The kind of cooking that we saw today,” she added, “was with a brilliant chef, who is also a fantastic person, and he showed everyone that recipes that at first seem complex can be produced (at home) in such an exciting, beautiful way. I really think that these are the kinds of opportunities that change minds and change the world–that you learn to live in harmony with the life around you.”

Feral said the more people realize how fine-tasting vegetable dishes can be, the more likely they will be to switch from animal-based diets. “Most people think that when a cookie or a cake is going to be served and it is called ‘vegan,’ that it is going to be like cardboard, and I think the so-called ‘health food’ of the 1970s is not the kind of food that you get today,” she said.

“So vegetarian cooking has become far more exciting– the opportunities you have for not only making your own, but finding ingredients that we didn’t even know were possible– it can be a totally gourmet experience, and really taste better than anything I ever ate as an omnivore.”

*

Matzo Ball Soup from 660 Curries

by Raghavan Iyer and Jeff Mandel

For the matzo balls:

1/4 teaspoon cumin seeds

1/4 teaspoon black or yellow mustard seeds

1/4 teaspoon fennel seeds

1 dried red Thai or cayenne chili, stem removed

1/2 cup matzo meal

2 extra-large or jumbo eggs, slightly beaten

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/2 teaspoon coarse kosher or sea salt

*

For the soup:

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 medium-size red onion, finely chopped

1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

2 to 4 fresh green Thai, cayenne, or serrano chilis, to taste, stems removed, cut in half lengthwise (do not remove the seeds)

8 cups low-sodium chicken (or vegetable) stock

1 large parsnip, peeled, ends trimmed, quartered

2 large carrots, peeled, ends trimmed, cut crosswise into 1-inch-thick pieces

4 medium-size to large ribs celery, ends trimmed, cut into 1/2-inch-thick pieces

1 teaspoon coarse kosher or sea salt

2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh cilantro leaves and tender stems

*

1. To make the matzo balls, heat a small skillet over medium-high heat. Add the cumin seeds, mustard seeds, fennel seeds, and chili, and cook, stirring them every few seconds or shaking the skillet very often, until the mustard seeds crackle and maybe pop, the cumin and fennel seeds turn reddish brown, and the chili blackens, 1 to 2 minutes.

2. Immediately transfer the nutty-smelling spices to a plate to cool. (The longer they sit in the hot skillet, the more they will burn, making them bitter and unpalatable.) Once they are cool to the touch, place them in a spice grinder and grind until the texture resembles that of finely ground black pepper. (If you don’t allow the spices to cool, the ground blend will acquire unwanted moisture from the heat, making the final blend slightly “cakey.”) Alternatively, use a mortar and pestle; it might work even better because of the small quantity of ingredients.

3. Transfer the reddish-brown, nutty-smelling spice blend to a medium-size bowl and add the matzo meal to it. Stir in the eggs, oil, and salt. Place the bowl in the refrigerator to allow the matzo meal to absorb the liquid and the mixture to chill, about 15 minutes.

4. Bring about 2 quarts salted water to a rolling boil in a large saucepan over medium-high heat. While the water is heating, place a heaping tablespoon of the chilled matzo blend in the palm of your hand. Shape it lightly (without compressing it tightly) into a ball, and set it on a plate. Repeat with the remaining matzo blend.

5. Once the water is boiling, gently slide the matzo balls into the pan. Reduce the heat to medium-low, cover the pan, and simmer, stirring very gently maybe once or twice, until the balls swell up and are firm-looking (akin to a piece of water- logged sponge), 20 to 25 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and keep it covered while you prepare the broth. (The matzo balls can keep in the water, refrigerated, for about 2 days. You can also freeze them for up to a month, drained and stored in an airtight, freezer-safe container.)

6. To make the soup, heat the oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Add the onion and stir-fry until it is soft but not brown around the edges, 2 to 4 minutes. Stir in the turmeric and chilis.

7. Pour in the stock, and add the parsnip, carrots, celery, and salt. Bring to a boil.

Drain the matzo balls, add them to the stock, and reduce the heat to medium-low. Cover the pan and simmer, stirring very gently maybe once or twice, until the carrots are fork-tender, 10 to 12 minutes. Remove and discard the parsnips and chilis.

8. Place two matzo balls in each soup bowl, and ladle some of the broth and vegetables over them. Sprinkle with the cilantro, and serve.

*

Next in the series. An interview with a Rancho La Puerta guest: Serene Jones, president of the Union Theological Seminary

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Very, very nice article.

Hi Rhagavan:

I will definitely try this matzo ball soup on my family… sounds delicious and different. Will give you a all the comments when they have tasted this new receipe.

Hope all is well.

Best, Rachele

I’m hungry! Tengo hambre. Yum!