By Eileen Wingard

PORTLAND, Oregon–Swiss-born composer, Ernest Bloch, is considered to be the greatest 20th century figure to incorporate Jewish motifs into his music. One may safely say that every recognized violinist, today, knows his Baal Shem Suite; every violist has studied the Suite Hebraique; and every cello soloist includes Bloch’s inspiring Shelomo in his or her repertoire. In fact, this year’s American String Teachers Association solo competition lists the Nigun from the Baal Shem Suite along with a movement from Bach’s unaccompanied Sonatas and Partitas as the two required selections for its violin contestants.

PORTLAND, Oregon–Swiss-born composer, Ernest Bloch, is considered to be the greatest 20th century figure to incorporate Jewish motifs into his music. One may safely say that every recognized violinist, today, knows his Baal Shem Suite; every violist has studied the Suite Hebraique; and every cello soloist includes Bloch’s inspiring Shelomo in his or her repertoire. In fact, this year’s American String Teachers Association solo competition lists the Nigun from the Baal Shem Suite along with a movement from Bach’s unaccompanied Sonatas and Partitas as the two required selections for its violin contestants.

During my recent visit with my daughter, Harriet, in Portland Oregon, l learned more about Ernest Bloch. His music has played an important role in my life and in the life of my concert violinist sister, Zina Schiff. I asked Harriet if we could visit Bloch’s home on the Oregon coast. I also requested that she try to arrange a meeting with Bloch’s grandson, Ernest Bloch II. I knew that she was acquainted with the Director of the Oregon Jewish Museum who was a friend of the junior Bloch. Harriet managed to fulfill both of my wishes.

First, the two of us drove to Agate Beach, north of Newport, in search of the house where the celebrated composer lived during the last eighteen years of his life and where he composed one third of his works. He and his wife, Marguerite, moved there in 1941, after their eldest son, Ivan, an electrical engineer, accepted a position with the Bonneville Power Administration. Ivan figured prominently in all the power company’s projects and was a highly respected industrial consultant. His parents sought peace, solitude and proximity to nature when they settled in this Agate Beach house with its beautiful view. Their idyllic dream was shattered when Japanese bombs dropped nearby following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Anxiety and fear disrupted their lives. Bloch’s creative juices seemed to dry up during the war years, flowing again only after D-Day.

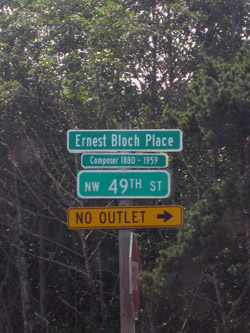

Although Harriet and I had the address of the Bloch house, it was set back from the street and difficult to find. When we finally located it, we discovered that there was no identification other than the address number. In fact, the building was not preserved as a historical monument, and it was not open to the public. It had been sold to a church in Salem, Oregon and was used as a retreat center. To our disappointment, we could not even enter the premises of the U-shaped structure. We took a few photos of the exterior and noted the street sign nearby that read, “Ernest Bloch Place,” designating a few feet of roadway ending at a cul-de-sac.

The next day, back in Portland, thanks to Harriet’s request to Judith Margles, Director of the Oregon Jewish Museum, I had the honor of meeting Ernest Bloch II, grandson and namesake of the renowned composer.

Arriving at the museum, Harriet and I were ushered into a room by the gracious museum director. We sat down at a large table. Ernest Bloch II, known to his friends as “Ernie,” soon arrived.

An imposing figure with a warm, open smile and bright blue eyes, Ernie spoke candidly about his grandfather. We related our disappointment that the Bloch House was inaccessible. He told us about its approval for designation as a historical monument. Were it so designated, the church would be restricted from making alterations to the premises.

When the composer died, Ernie was twenty-one and, since he and his younger sister were the only grandchildren living in Oregon, he developed a close relationship with the elder Bloch, even driving him to doctors’ appointments during the composer’s final years.

Ernest Bloch encouraged his grandson’s independence, in spite of the youngster’s physical handicap from a bout with polio at age five. With the use of crutches, Ernie would maneuver down the slopes from the house perched on a cliff overlooking the ocean, arriving at the sandy beach below, often ahead of his grandfather.

One of the composer’s hobbies was collecting agates on the beach. Ernie would help his grandfather hunt for the colorful stones. The pair would then polish them in Bloch’s makeshift lapidary workshop, adhering the agates to a cigar box stick with sealing wax to protect their fingers from being scraped by the polisher.

I brought along a copy of my sister Zina Schiff’s, highly acclaimed recording of the Bloch Violin Concerto, the Baal Shem Suite and Suite Hebraique with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and presented it to Ernie. He was pleased to receive this gift, since he did not have Zina’s recording, and in his mission to preserve his grandfather’s legacy, he has attempted to collect all the professional recordings of Bloch’s music.

Ernie, in turn, gave me two polished agates, one for Zina, and one for me. I was deeply moved, realizing that these beautiful stones were once fingered by the man who wrote some of my favorite music.

I told Ernie about Zina’s strong relationship to his grandfather’s music, including the performance of the Baal Shem Suite with the Philadelphia Orchestra when she won their Junior Auditions while a student at the Curtis Institute. It had not been played with the orchestra since Mischa Elman performed it thirty years before. I also mentioned her experiences performing that work in Moscow and throughout Europe and the United States.

Ernie spoke about another of Bloch’s interests: photography. The Oregon Jewish Museum had a recent exhibit of Bloch’s photographs. The composer carried on a lengthy correspondence with the great California photographer, Ansel Adams, and he was close friends with the famous photographer, Alfred Stieglitz and artist, Georgia O’Keefe, visiting them several times in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Bloch learned much about photography from Stieglitz.

Ernest Bloch not only wrote music, he was an incessant letter writer. Over 6,000 of his letters have been collected, most of which are housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Others are at the Cleveland Institute of Music, where he was founding director from 1920-25 and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, which he also founded and directed from 1925-30. The Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library at the University of California, Berkeley also houses some letters and manuscripts in their Ernest Bloch archive. His letters reveal a man of many facets and multiple interests in science, literature, philosophy and the arts.

Ernie told me of the 2009 world-wide commemorations of the fiftieth anniversary of Bloch’s death. He travels frequently throughout the US, and to Europe and China to attend Bloch events. Recently, he attended a United Nations Association International Choir performance in Houston Texas where a choir of singers from throughout the world performed Bloch’s Sacred Service.

In 2007, Bloch’s grandson participated in an Ernest Bloch Conference at the University of Cambridge, England. He was one of the featured speakers. England has an active International Ernest Bloch Society as do Switzerland and Israel. There, the society is headed by the brilliant conductor, Dalia Atlas. Israel even issued stamps commemorating the two most famous Jewish composers of the 20th Century, Ernest Bloch and Leonard Bernstein.

Although neither Ernie, nor his father were musicians, Ernie, a philanthropic consultant, has devoted much of his time and energy to promoting the legacy of his illustrious grandfather.

Bloch’s second child, Suzanne, followed in her father’s footsteps, becoming a musician. She was a Renaissance specialist, a lute soloist, the founder of the American Lute Society, and she taught for forty-five years at the prestigious Juilliard School in New York City.

When Zina programmed Bloch’s Poem Mystique for her Metropolitan Museum Recital with pianist Vladamir Sokoloff, she contacted Suzanne Bloch, who kindly gave her some revisions made by Bloch after the work was published. Suzanne also attended that recital.

Bloch’s youngest child, Lucienne, was an artist and photographer. She and her husband befriended Diego Rivera when he worked on a mural commissioned by John D. Rockefeller. A figure of Lenin in the mural angered Rockefeller; however, Rivera refused to remove it and was fired. Before the raging Rockefeller destroyed the mural, Lucienne made a photograph of the work.

As we continued our conversation, I mentioned that Bloch’s Avodah was on Zina’s most recent program last May 7 in San Francisco, when she performed at Temple Emanu-El, the temple whose rabbi commissioned Ernest Bloch to write his Sacred Service.

It was that year of the Sacred Service commission, 1930, that the Haas (of Levi Strauss fortune) and Stern Families of San Francisco bestowed an endowment on Bloch, enabling him to devote himself solely to composing for the following ten years. He took his wife back to Geneva, Switzerland where he wrote the Sacred Service.

Although Switzerland was ostensibly neutral, the Nazi Nuremberg Laws and the upsurge of anti-Semitism in neighboring Germany brought fear into their hearts. In 1937, the Blochs left the rising tide of Nazi power and returned to the United States. He and his wife relocated to the only house they ever owned, at Agate Beach, Oregon, on the Pacific Coast.

While Bloch is best known for his Jewish works, he did not want to be known solely as a Jewish composer. In fact, his Jewish-titled compositions are but a small portion of his seventy-three published works. I recall performing one of his Concerto Grossi and some of his other beautiful chamber works.

My most treasured Bloch memories were when I played Shelomo with the Festival Orchestra at the Berkshire Music Festival in Tanglewood in 1950. The concert was being performed in the outdoor Tanglewood Shed and it began to thunder. It was as if the heavens above were participating in Bloch’s magnificent score. I also remember playing in the San Diego Symphony when we accompanied Ralph Kirshbaum in his moving performance dedicated to the memory of Israel’s Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, following his assassination. Most of all, I treasure the memory of playing in the San Diego Symphony when we accompanied my sister, Zina Schiff, in her stirring performances of Bloch’s Violin Concerto.

I was thrilled to have the opportunity to meet Ernest Bloch II. I learned more about his grandfather, a brilliant genius whose music I have played and loved, and I met a man whose dedication to his grandfather’s legacy and whose warm and generous heart is an inspiration to all who know him.

*

Wingard is a freelance writer and former violinist with the San Diego Symphony. She may be contacted at eileen.wingard@sdjewishworld.com