By Donald H. Harrison

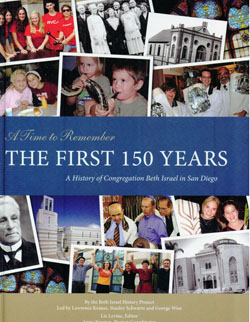

SAN DIEGO– There’s a new resource in town for anyone interested in the Jewish experience in San Diego: A Time to Remember: The First 150 Years, a beautifully printed, hard-cover book detailing the experiences thus far of Congregation Beth Israel and its historic forerunner, Congregation Adath Jeshurun.

SAN DIEGO– There’s a new resource in town for anyone interested in the Jewish experience in San Diego: A Time to Remember: The First 150 Years, a beautifully printed, hard-cover book detailing the experiences thus far of Congregation Beth Israel and its historic forerunner, Congregation Adath Jeshurun.

The book was written by members of the Beth Israel History Project, led by Lawrence Krause, Stanley Schwartz, and George Wise, and including a variety of other contributors drawn from the staff and members of the congregation. Liz Levine served as editor and Anna Newton as project coordinator.

Utilizing board minutes, issues of the congregational newsletter Tidings; and the memories of long-active congregants, members of the History Project put together a remarkable 121-page summary of one Reform congregation’s experiences over a century in a half. The main text was followed by some 16 pages of afterword, appendices and endnotes, but, unfortunately for future researchers, there was no index.

While we must be careful not to infer that Beth Israel’s changes in attitude over the decades concerning the roles that women, music, ritual, and Zionism should play in American Jewish life necessarily typifies the entire Reform movement, the book addresses in a straightforward manner just how these issues played out at Beth Israel. It also details the growth of congregation-affiliated school programs, auxiliaries like the Men’s Club and Women of Beth Israel, concurrent worship services for a more conservative-leaning minyan; colorful fund-raising events, and the fostering of tikkun olam programs, especially in the area of feeding the hungry.

Given that the book had to go through a committee, there is more candor than perhaps one might expect about some issues, including the fact that at least three rabbis were fired over the years for their sexual infidelities, while others left for such reasons as to earn more money, or in disputes over congregational worship styles. Even so, some other pulpit rabbis’ mysterious reasons for leaving Congregation Beth Israel were left unstated.

Including the incumbent spiritual leader, Rabbi Michael Berk, there have been 20 senior rabbis, all of them men, over the 150 years, with some long periods when lay leaders coped without rabbis. During the century and a half there also were an indeterminate number of other rabbis, some of them women, who served as assistant pulpit rabbis or educators, as well as Rabbi/ Cantor Arlene Bernstein who studied for and earned her rabbinate while serving as the cantor.

Forty -four congregational presidents, some of them having served non-consecutive terms, are known to have served over the same period, with eight of them being women, starting with Joan Jacobs in 1976 and including the present president, Emily Jennewein.

We learn in this volume how there were splits in the congregation leading to the establishment of other congregations, and how, in one case, there was also a reconciliation leading to merger. The book details the experience of Jews in San Diego from the time of Adath Yeshurun’s organization in 1861 to the opening of the first temple building in time for the High Holy Days of 1889, with the new congregational name of Beth Israel.

It goes on to tell how the congregation grew during San Diego’s boom periods and withered during its bust times; relates the story of the congregation’s second home with its Moorish style architecture at Third and Laurel Streets (now the home of Conservative Congregation Ohr Shalom), and provides insight into how demographics influenced the selection of Beth Israel’s third and current Jerusalem-style campus at 9001 Towne Center Drive in the La Jolla/ University City area. At one time, Beth Israel had considered opening a satellite campus in Rancho Santa Fe, but eventually decided to sell that property.

The book discusses frankly the demise of Congregation Beth Israel’s Day School, acknowledges contributions of key staff members including longtime program director Bonnie Graf, and in general provides members with lots of nachas, and historians with a resource to closely check when desiring to learn more about some of the members of San Diego’s oldest and largest congregation.

Historians tend to prefer primary sources over secondary sources, because the former are those documents that tell what happened in the participants’ own words. Secondary sources, in contrast, often are rehashes of primary sources, and sometimes inadvertently pass on errors or false assumptions made by previous historians.

Beth Israel’s sesquicentennial anniversary book will be valuable to future historians because it is a mixture of both primary and secondary sources. It is clear that a lot of thought and hard work went into it.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted at donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com