By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – The Japanese community of San Diego held a cherry blossom festival last weekend at the Japanese Friendship Garden in Balboa Park. It was an event for all the senses. The colorful costumes of the children and the koi in the pond pleased the eye. Japanese music gratified the ear. Games and souvenirs appealed to the touch. A medley of Japanese foods excited the tastes. And, a traditional tea ceremony satisfied the senses of order and aesthetics while Japanese-style books intrigued the intellect.

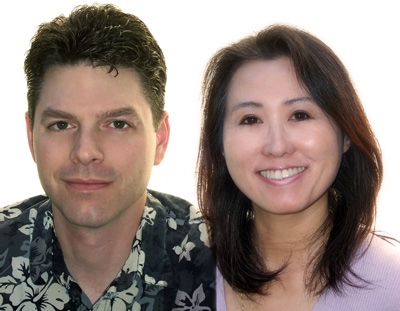

Sarah Server Mondragon, owner of Soul Juice, a San Diego company that produces green-inspired events for children, was on hand to represent her Northern California cousins who own another child oriented business. They are David Battino and his wife, Hazuki Kataoka, who publish kamishibai-style books that help to make reading to audiences of children simpler and more fun.

When they were single, Battino and Kataoka both had Jewish roommates who invited them to come along on a Big Bear skiing trip sponsored by a young Jewish singles group in Los Angeles. From a religious and cultural point of view, it was perhaps a somewhat greater adventure for Kataoka, who was raised in Tokyo, than for the American Battino, whose father is a Jew of Greek background and whose mother is Presbyterian.

When they met on the skiing trip, the two found much to talk about. Battino had spent a year in Japan on a Luce scholarship following his graduation from Oberlin College with a major in philosophy. The scholarship had enabled him to spend a year in Tokyo where he worked for a Japanese record company. Kataoka had come from Tokyo to Los Angeles, where she had worked at a Japanese-language newspaper.

Now married for 18 years, the couple moved to northern California. In a telephone interview, Battino said they had found life in Los Angeles “claustrophobic.” Remembering the kamishibai method of story telling which was so familiar to her in Japan, Kataoka was surprised that school teachers in the United States still read bound books which they had to twist around for their young audiences to see.

The kamishibai style book is printed on posters, which are held up for students to see while the teacher reads the story from the back of the stack of posters. The narration for poster #1 is printed on the back of the last poster in the set. The teacher reads while facing her audience and is therefore able to make eye contact. When she completes the narration for Poster 1, she moves that poster to the back of the stack and then reads from its reverse side, where the narration for Poster 2 is printed. In this way, she moves effortlessly through the story, never losing track of her audience.

Mondragon allowed me to read to some children including her daughter Lilly the story of Momatoro (Peach Boy), which is a favorite Japanese tale that is also quite well known in other parts of Asia. In fact, my daughter-in-law, Hui-Wen Harrison, said she remembers hearing and enjoying the story as a child growing up in Taiwan. I had accompanied her, my son David and grandson Brian to the festival.

In the story, an old couple despairs that they never had a child. Then one day, the woman saw a giant peach floating down the river. Retrieving it, she thought it would make a tasty dinner, but when she split it open she found a beautiful boy inside. The boy grew up and came to resent the ogres who lived nearby and stole everyone’s possessions. He decided he would confront the ogres and get the possessions back. On his journey to the land of the ogres, he was joined by various animals who also had been wronged by the ogres. Working as a team, they were able to defeat the horrible head ogre in combat, thereby winning the ogres’ cooperation in returning the goods to the rightful owners.

The posters displayed during the telling of the story measure 10 inches by 13 inches, and I could tell that even if the children were not listening to every word I was reading, they most certainly were fascinated by the vivid and colorful illustrations on the front of the posters. Although there was dancing, music, games and food in the vicinity, the children stayed rooted in their spots, listening to the story until its conclusion.

Next, they published Jack and the Beanstalk, which proved to be a bigger hit in Japan—where the English story was exotic—than in America, where it was very well known.

They went back to a Japanese story for their third book, Moon Princess, which Battino said he and his wife particularly liked because this was a story of an independent young princess, not one who had to be rescued from a tower or be otherwise dependent on a man.

In fact, all the young men pay court unsuccessfully to the princess, who rejects each one of them. The reason for her standoffishness was that she was not from the earth, but from the moon, and had to return to her home.

Battino and Kataoka are frequently booked for parties, festivals and other entertainment events to perform the stories for children—“perform” being more accurate than “read” to describe the way the stories can be delivered when there is direct eye contact between storyteller and audience.

Having experimented with Jack and the Beanstalk and also with a Russian tale, Battino says he prefers the authenticity of using the Japanese story-telling art for Japanese tales.

He noted during our conversation that there are some commonalities to traditional Japanese folk tales. Typically they begin with an old man and an old woman. And there is a bit of the supernatural. Momatoro sprung from a peach, whereas the Moon Princess emerges from inside a bamboo plant.

The publishing company created by Battino and Kataoka selects and writes the folk stories—sometimes editing them to make them less violent. They also commission the artists who draw the storyboards. Their story about Peach Boy is currently sold out, and in the second edition, says Battino, more of the illustrations will focus on Peach Boy’s animal friends.

Recalling how intently the children I read to followed the story of Peach Boy, I decided it was a lucky thing indeed that the two publishers’ Jewish roommates had persuaded them to come along on a ski trip.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World