By Rafael Medoff/JNS.org

WASHINGTON, D..C. — “We didn’t know you couldn’t organize a mass rally in four days, and sometimes if you don’t know, then you just plunge ahead—and you do it.” So says Glenn Richter, one of the organizers of the rally in New York City, 50 years ago on May 1, which launched the Soviet Jewry freedom movement.

In the spring of 1964, not many American Jews were paying attention to the plight of their three million coreligionists in the Soviet Union. But Yaakov (Jacob) Birnbaum and Morris Brafman were.

Their personal experiences had made them keenly aware of the commandment to not stand idly by as fellow Jews were persecuted. Birnbaum, 37, was born in Germany but raised in England, to which his parents fled from the Nazis. Brafman, 58, was a refugee from Austria. His nephew—prominent criminal defense attorney Ben Brafman—has written about how on Kristallnacht, his father, Sol, and uncle Morris “ran into a burning synagogue and rescued a Torah that would otherwise have been consumed by the flames.” In 1960, the Brafman brothers, living in New York, established the first fledgling Soviet Jewry group, the American League for Russian Jews.

In April 1964, after reading reports in the press about the mistreatment of Soviet Jews—including the Kremlin’s refusal to allow Jews to obtain matzahs for that year’s Passover holiday—Birnbaum and Brafman decided to call a meeting on the campus of Columbia University to brainstorm about the situation. Glenn Richter, a Queens College sophomore, was one of those who attended.

Richter told JNS.org that about 150 students attended that meeting—a surprisingly large number, considering the Soviet Jewry issue was almost completely unknown at that point. “It was an amazing scene, kind of electrifying,” he recalled. “We had the indignation of college students, we were outraged over an injustice and anxious to do something.” One of the students suggested they hold a rally outside the Soviet Mission to the United Nations, on Manhattan’s 67th street, on May 1—just four days away.

“Sometimes enthusiasm makes up for experience,” Richter said. “Nobody in that room had the experience to know how difficult it would be to organize a serious rally in just four days—so nobody thought it was impossible. We just jumped into it.”

Birnbaum was instantly attracted to the rally proposal because of the symbolism of holding it on May Day—the international holiday of the Communist movement. Rebuking the Soviets on their own holiday was exactly the kind of irony that he believed would attract public and media attention. And he was right.

“Symbolism was everything to us,” Richter noted. “Many of us were active in the black civil rights movement, where we were constantly looking for symbolic ways to dramatize our cause. When we started organizing for Soviet Jewry, we borrowed heavily from what we learned in the civil rights movement.” Richter himself had been a regular volunteer in the New York offices of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a leading civil rights activist group. Later, anti-Semitic black nationalists took over SNCC and many of its Jewish members departed. Some ended up in the Soviet Jewry movement.

“For four days, we ran around like crazy, pasting up posters, handing out leaflets on college campuses, ‘talking up’ the rally everywhere we could,” Richter said. “We really had no idea how many people would show up. When the day arrived, we watched in amazement as the people started coming, and then more, and then more, until more than a thousand students were marching up and down the street. It was an incredible moment.”

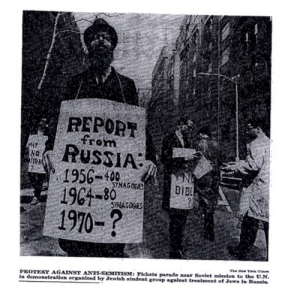

The large photograph and article that appeared in the next day’s New York Times—on page 2, to the students’ great surprise—reveals a lot about the young protesters. They are well-dressed, picketing in calm, orderly fashion, holding placards with well-thought-out slogans. The sign that is most prominent in the photo is remarkably informational: “Report from Russia: 1956 – 400 Synagogues; 1964 – 80 Synagogues – 1970 – ?”

“We understood that it was, first of all, a battle for public opinion,” Richter explained. “Nobody had heard of the issue. We had to educate the public. The slogans were carefully planned. The students were instructed to be on their best behavior. We were trying to make Soviet Jewry into an issue that Americans would take seriously.”

That would not happen overnight. There would be decades of demonstrations and other protests—by the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, led by Birnbaum and Richter, by other activist groups, and eventually by the mainstream Jewish organizations. There would be battles in Congress and empty chairs set at Passover seders and American Jews sneaking into the USSR to help Soviet Jewish refuseniks. It would be one of the proudest chapters in American Jewish history. All that had to start somewhere—and it did, 50 years ago on May 1, with a handful of college students who did the impossible because they didn’t know it couldn’t be done.

*

Dr. Rafael Medoff is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies…. Preceding provided by JNS.org, which is sponsored on the pages of San Diego Jewish World through the generosity of Dr. Bob and Mao Shillman. … San Diego Jewish World seeks sponsorships to be placed, as this notice is, just below articles that appear on our site. To inquire, call editor Donald H. Harrison at (619) 265-0808 or contact him via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com