-Third in a series —

By Donald H. Harrison

TEMECULA, California – Attorney and writer Erle Stanley Gardner invented “Perry Mason,” the fictional defense lawyer of television and pulp fiction fame, who most people my age (68) can’t think of without remembering the actor who played him on television, Raymond Burr.

Gardner also was fascinated by the real life “thrill” murderers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two law students who tried in 1924 to commit the “perfect crime” – that is, one that could never be solved. After botching the cold-blooded killing of young Bobby Franks, the two Jewish friends were defended in a sensational trial by Clarence Darrow, and after changing their pleas to guilty, narrowly avoided the death penalty — although Loeb subsequently was stabbed to death by a fellow inmate at Joliet Prison.

Gardner, who lived in Temecula, wrote a book review for the New York Times in 1956 about Compulsion, a fictionalized account of the case written by Meyer Levin that later was made into a movie starring Dean Stockwell, Bradford Dillman, Orson Wells and E.G. Marshall. After winning parole in 1958, Leopold published Life Plus 99 Years, a reference to the length of the sentence the judge in the case had recommended. The book was Leopold’s own account of the murder—for which Gardner supplied an introduction.

Such is the “Jewish connection” to Erle Stanley Gardner, whose life (albeit without reference to the Leopold & Loeb case) is the subject of a permanent exhibit in the Temecula Valley Museum at 28314 Mercedes Street, just a few turns from the Interstate 15 exit at Rancho California Road.

__________________

__________________

I-15 Jewish Sightseeing

__________________

There is an even more tangential connection resulting from Gardner’s friendship with cattle rancher Malin Vail with whom the mystery writer liked to play poker and toss back a few drinks. Vail had purchased the land upon which the adobe store of pioneer Jewish merchant Louis Wolf had been built. Wolf, a Jew from the Alsace region of France, was a major influence on the development of Temecula (which is named for a local band of Native Americans.) A section of the city east of its Old Town is known as the Wolf Valley.

Today, Wolf’s adobe store is being restored as part of a 4 ½ acre historic project that Riverside County’s Board of Supervisors required of the developers, Arteco Partners. A large mural of seven Vail Ranch cowboys on the wall of a building behind the adobe was photographed by Gardner.

In another section of town, Wolf’s tomb, surprisingly, sits in a fenced field at the end of a residential cul-de-sac. Whatever they may say about having a private one-family cemetery next door, the occupants of the two homes adjacent to the tomb can say, no doubt, that “the Wolf family are quiet neighbors.”

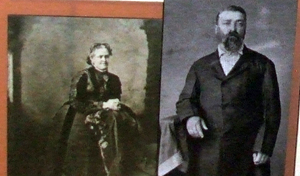

Wolf, after trying his luck in San Francisco, settled in Temecula in 1857, operated a trading post, where most of his customers were local Luiseno Indians. He became involved in city and school board affairs, and became so influential he sometimes was referred to as the “King of Temecula.” His wife, Ramona, was half Chumash Indian, who took an interest in the local Temecula Band of Indians.. According to Temecula Valley Museum docent Steve Williamson, it was Ramona Wolf who told author Helen Hunt Jackson during her visits in 1881 and 1882 a story about how the Temecula Indians were evicted from their lands. Hunt, researching the treatment of Mission Indians up and down California, incorporated the story into novel, Ramona, which was both a romance novel as well as a plea for better treatment of California Indians.

Some people think that Ramona Wolf was the model for the heroine of Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel, but Williamson is unconvinced. He says “Ramona” was a fairly common Native American name, and whereas Mrs. Wolf may have been one influence on Jackson, it’s probable that the fictional Ramona was a composite character. Whoever Ramona was named for, the book published in 1884 was the impetus ten years later for the renaming of “Nuevo,” a town in the San Diego County foothills, to its present name of “Ramona.” This, incidentally, was at the insistence of land developer Milton Santee, for whom the San Diego County city of “Santee” is named.

“Ramona” in 1936 became the subject of a movie starring Loretta Young as Ramona and Don Ameche as her Indian lover Alessandro—a movie that Williamson likes to describe as a cross between “Cinderella” and “Romeo and Juliet.” In San Diego, the Casa de Estudillo in what is today Old Town San Diego State Park was once marketed as Ramona’s Wedding Place, after the hacienda to which the fictional couple fled to be married in San Diego. Today, the Ramona story still is produced annually as a pageant in the Southern California City of Hemet.

Wolf’s connection through his wife to Helen Hunt Jackson was not his only claim to fame. As a merchant, he extended credit to many of the cash-poor residents of Temecula and later when the railroad came to town, spurring the growth of the granite and cattle industries, he was able to supply labor to the railroad. According to Williamson, the local folks would pay off their debts to Wolf by doing temporary labor either for each other or these growth industries. The railroad was a mixed blessing for Wolf; whereas it brought economic development to Temecula, it also caused the commercial center to shift from the area of his adobe trading store several miles to the west, where Old Town Temecula stands today, a warren of souvenir shops, restaurants, and late 19th and early 20th century buildings.

My grandson Shor and I enjoyed lunch with Williamson at The Bank, a Mexican restaurant built in the building that once served as the Temecula First National Bank. Decorations were still up in the restaurant for the celebration of the bank’s 100th anniversary on June 10, 2014, a centennial that included souvenir chocolate gelt with a picture of the bank stamped on the gold tin foil cover. In addition, there was a reenactment of a 1930 bank robbery by Vail ranch hand Miguel Diaz, who told a woman he met in a bar that he was an airplane pilot. According to Williamson, when the woman said she’d like to go up in his plane, Diaz decided he’d rob a bank and buy a plane. Trouble was, being a local, he was recognized and was soon captured following an automobile chase, without any chance to spend the money, much less further impress the woman. As in the original incident, a man getting a shave at a barber shop across the street, ran outside with his face full of lather during the reenactment, to see what all the commotion was about as 1930 era automobiles roared out of town.

My grandson Shor and I enjoyed lunch with Williamson at The Bank, a Mexican restaurant built in the building that once served as the Temecula First National Bank. Decorations were still up in the restaurant for the celebration of the bank’s 100th anniversary on June 10, 2014, a centennial that included souvenir chocolate gelt with a picture of the bank stamped on the gold tin foil cover. In addition, there was a reenactment of a 1930 bank robbery by Vail ranch hand Miguel Diaz, who told a woman he met in a bar that he was an airplane pilot. According to Williamson, when the woman said she’d like to go up in his plane, Diaz decided he’d rob a bank and buy a plane. Trouble was, being a local, he was recognized and was soon captured following an automobile chase, without any chance to spend the money, much less further impress the woman. As in the original incident, a man getting a shave at a barber shop across the street, ran outside with his face full of lather during the reenactment, to see what all the commotion was about as 1930 era automobiles roared out of town.

*

Williamson, a retired letter carrier for the Post Office and amateur historian, had numerous stories to tell about Erle Stanley Gardner. Born in the Malden suburb of Boston, Gardner moved to the West Coast when he was 10, living in Oregon, Alaska and California during his youth. He obtained a law degree by examination, working in Oxnard and Ventura before his first novels were published. Originally, Gardner had planned to name the mystery-solving lawyer “Ed Stark,” but, according to Williamson, his publisher thought the name too hard-edged. They asked him to think of another name. Gardner thought perhaps the character could be called “Stone,” but that also seemed hard-edged. But “Stone” made him think of a “stone mason” and then Gardner remembered The Youth’s’ Companion, a weekly newspaper distributed to school kids that he had read while still living in Malden, Massachusetts. The newspaper for kids was published by the “Perry Mason Publishing Company,” and thus “Perry Mason” was the name he gave his central character. One issue of The Youth’s Companion is displayed on a wall of the upstairs Gardner exhibit.

Williamson said that Gardner liked the law, particularly legal strategy, but he hated being indoors. When he realized that he could support himself writing books – actually he didn’t write them, he dictated them, punctuation and all for transcription by his secretaries – Gardner made the decision to purchase some of California’s back country, which he loved to explore on his way to Baja California, which was another of his great loves. He initially purchased 150 acres of property in the Temecula area and then added adjoining parcels, until he eventually aggregated the 3,000-acre Rancho de Paisano, which he left more or less undeveloped. He didn’t want to raise cattle or sheep, simply to have open space—“elbow room” – within which to wander, according to Williamson.

There’s a photo in the museum of Gardner in a camp chair reciting a Perry Mason story to a dictation machine. Williamson said Gardner tried to dictate at least 100,000 words a month, and his output was prodigious. According to a museum brochure, he wrote 151 books, including 82 Perry Mason mysteries, which were the bases for 271 Perry Mason television episodes. He used pseudonyms for some of his other books, the best known alias being A.A. Fair.

Gardner, born in 1899 died in 1970. Today, most of his manuscripts are in the library at the University of Texas at Austin. Williamson said he researched the connection between that university and Gardner but found no formal relationship. The reason the University of Texas got the manuscripts might have delighted the fictional Perry Mason: Simply put, the museum “asked for them.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com