By Donald H. Harrison

OCEANSIDE, California – Surf historian Jane Schmauss vividly recalls the day she waited expectantly as the telephone rang at the home of Kathy Kohner Zuckerman, a legendary figure in the development of surfing as a popular sport.

“Hello?” responded the voice on the other end.

“Hello,” said Schmauss. “Is this the real Gidget?”

There was a pause on the other end. “Who wants to know?” asked Zuckerman.

Schmauss explained that she was among a group of surfing enthusiasts in San Diego County who had started the California Surf Museum, which was trying to preserve both the history and the legends of surfing.

“Gidget” was the nickname young surfers had given to Kohner in the late 1950s when she was a 15-year-old girl hanging around the beach at Malibu. It was a contraction for “Girl Midget.”

The pop culture figure told Schmauss that in the years since her father, Frederick Kohner, had written the best-selling book Gidget: The Little Girl With Big Ideas, based on her diaries, and after the television sitcom Gidget, which had launched the acting career of Sally Field, she had been living a quiet life, working in a book store and being married to Yiddish professor Marvin Zuckerman.

That first conversation occurred sometime in the 1980s when the surfing museum movement—which now has blossomed into a worldwide phenomenon—was just getting underway, said Schmauss, who was in the group of the museum’s founders.

Once surf museums started to spring up, Schmauss added, “people were curious to see the real Gidget, to get her diary, to her her recollections. She speaks very well, she’s a very capable, very entertaining guest lecturer. From that time until now, they fly her all over the world to talk about the music, the personalities, and her own experiences of that time.”

Sam Zugner, a surfing semi-professional who supplements his income by working at the museum, commented that he has a copy of the book Gidget on which the cover illustration is of a young Kathy Kohner. After Field became the personification of Gidget thanks to the television series, new book jackets had Field’s photo, rather than Kohner’s, he recalled. His particular edition of the book, therefore, is quite a collector’s item.

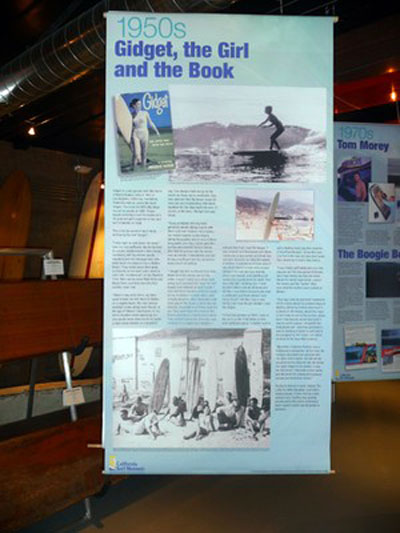

The lives of Kohner and other legendary surfers and surf enthusiasts are described in the museum on posters that follow the development of the sport from its earliest days when George Freeth and Duke Kahanamoku were popularizing it in the early 20th century to modern times when Lisa Anderson and Kelly Slater are inspirations for a new generation of surfers. The museum also displays numerous surfboards ranging from “Makai,” a surf board 9’8 in length that was owned by Kahanamoku to Anderson’s lightweight 5’11 board, personally autographed.

Midway through the exhibit is the story of Kohner, whose family went regularly from their home in Brentwood to the beach at Malibu. Rather than sit with her parents and engage in long conversations with their friends, Kohner recollected in a forward to her father’s book, “I would wander up the beach, taking long walks.” She came upon the “surfers who dwelled beside Malibu Pier. Watching them ride the waves was incredible. I immediately decided to buy a surfboard and try my best to learn the art of surfing. I bought my surfboard from Mike Doyle for $30 and hit the water. I wasn’t really sure what I was doing but I watched the boys on their boards and imitated as best as I could. I also started to socialize with the same group of surfers, mostly male, and actually became rather fascinated with their way of life. It was a most alluring life style, especially to a 15-year-old girl.”

She told her parents about the boys who lived on a shack on the beach and who lived for nothing more than to go surfing. As a Hollywood screenwriter, her father recognized a good story when he heard one. In just six weeks he converted her diary into the novel that helped to popularize the sport. With the emergence of surf music—particularly as popularized by the Beach Boys—surfing became a permanent part of the California culture.

Chasing down the stories of the sport is what Schmauss, a former school teacher, just loves to do. Prevented by arthritis from surfing herself, she nevertheless has become as immersed in the subject matter as a surfer deep within a “tube” experiencing a cresting wave.

“The thing I get time and time again from the older surfers is the joy and passion and fun of catching a wave, and optimally sharing that moment with your friends,” she said. “Every wave is different. It can’t be repeated. And every one is a gift.”

Schmauss said she has come to appreciate that there are “people who surf” and then there are “surfers,” the latter category being an honor that relatively few attain.

She told of meeting a 96-year-old woman in Hawaii, who “lives next to the beach, next to the ocean, listens to its rhythm, knows the weather, the sight of a wave, the shape of the wave, the feel and the smell and the clutch of the wave, and she carries it in her bones.” The nonagenarian doesn’t surf anymore, hasn’t in more than 30 years, “but she is a surfer and she will always be.”

Asked what she hopes visitors who come to the museum at 312 Pier View Way in Oceanside will take away from the experience, Schmauss responded she would like them to understand “how much fun surfing is.”

That means visitors who aren’t quite sure what it means when something is described as “gnarly,” need not feel intimidated. Museum personnel enjoy teaching the uninitiated about the sport’s legends and lingo. “Gnarly,” by the way, means bad—like a wave on which a surfer “wipes out.”

In addition to its permanent exhibit, the museum sponsors special exhibits and special events. From March 2010 to the end of February 2011, for example, an exhibit on the women of surfing is planned, to which guests will be invited like “Gidget” and Lisa Anderson (who in the late 1980s dropped out of high school, traveled from Florida to California, and proceeded to win honors as ‘rookie of the year’ of surfing’s Professional Women’s World Tour.)

At a museum-sponsored festival two years ago featuring the 1966 classic surfing movie, The Endless Summer, writer/ director Bruce Brown showed up with his son and grandson. Poster-maker John Van Hammersville, whose works on enamel are on display at the museum, also showed up, as did cast member Mike Hynson and its music composer Gaston Georis.

The festival was a day that both surfers and people who surf were in their element.

*

Harrison is the editor of San Diego Jewish World. This article appeared previously on examiner.com