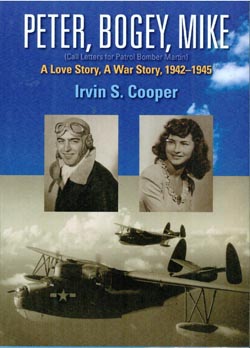

Peter, Bogey, Mike: A Love Story, A War Story, 1942-1945 by Irvin S. Cooper, ©2014 Capitola Book Company, ISBN-13: 978-0-932319-17-3, 289 pages, retail price not listed.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—I ran into author Irvin S. Cooper, a Los Angeles-based nonagenarian with a remarkable memory of his World War II experiences, at the San Diego Jewish Book Fair, which he attended with his daughter, Kitty, who lives in Rancho Bernardo. I told them that I would try to read the book once the crush of the Book Fair was over.

SAN DIEGO—I ran into author Irvin S. Cooper, a Los Angeles-based nonagenarian with a remarkable memory of his World War II experiences, at the San Diego Jewish Book Fair, which he attended with his daughter, Kitty, who lives in Rancho Bernardo. I told them that I would try to read the book once the crush of the Book Fair was over.

I’m glad I made that commitment, because in a clear matter-of-fact style, Cooper tells in his book what it was like falling in love as war was breaking out, getting married, living together in communities near various naval training stations, at least one of which was none too friendly to Jews, and then being separated by the war and the knowledge that they might not ever see each other again.

Cooper’s book also is an account of the fastidious training the Navy gave to its Patrol Bomber Martin (PBM) pilots, in which, during the last chapters of World War II, Cooper flew in the Pacific theatre, hunting for Japanese submarines, skirmishing with enemy aircraft, and fishing felled American pilots and crew members from the ocean.

There’s a saying, which I don’t believe, that “no man is an atheist in a fox hole,” but I do believe that times of battle and times of stress can prompt us to reflect on our roots, and the meaning of our lives, as Cooper did on his final light as a cadet, before being designated as a Naval aviator.

“Why at this time, on this particular flight, did my inner reflections cause my Jewish heritage to come to the fore?” he wrote. “I was a non-religious youth who went through a limited after-school religious exposure, but I never had a problem being Jewish. I had belonged to a Jewish Boy Scout troop, became an Eagle Scout, and competed equally with Scouts of all ethnic groups. My feelings toward my country were as strong as anyone’s. Growing up in a depression and hearing that all Jews were rich and controlled the banks was a mystery to me. My mom was a single mother and struggled to keep us together by renting a room in an older couple’s home. She had been raised in a Jewish orphanage in New York, and she fought to keep us together rather than having me repeat her childhood…”

Once, when Cooper ran a 103-degree fever while he and his wife Elaine were visiting Norfolk, Virginia, he was hospitalized and Elaine needed to find a place to stay. A woman named Nellie, who seemed like a kind nurse’s aide, invited her to stay with her and her husband in the room that their son had vacated to serve aboard ship as a Navy ensign. Elaine accepted, and all went well until the woman’s husband asked Elaine whether she, like the jewelers named Cooper in Norfolk, was also Jewish. Yes, she replied.

“The overwhelming silence that followed left Elaine confused,” author Cooper related. “She stood there. They stood there. There was an awkward silence. Elaine excused herself and walked timidly back into the guest bedroom. Nellie looked at her husband, shocked and bewildered. A Jew in their home? Elaine caught her words as she closed the door. ‘And to think I just changed the linens.’”

After retreating to the bedroom, Elaine wondered if she should leave, but it was the dead of night, she was a long way from the hospital, and she knew no one else in Norfolk. She spent an uncomfortable night, barely sleeping, and when morning arrived, she found the couple had already had their breakfast without her. She wasn’t invited to join them, with Nellie explaining, “I know Jews don’t eat bacon.”

There was an uncomfortable ride back to the hospital for Elaine, who never before had experienced such anti-Semitism. But she didn’t forget her manners. She subsequently purchased a box of chocolates and sent it to her sullen hosts, with a note saying “thank you for your hospitality.” She would not sink to their level.

Irwin Cooper’s most unforgettable war experience was flying nearly 1,000 miles to a spot on the Yellow Sea where a Japanese task force was assembling. The PBM sea planes flew close to the ocean, below enemy radar, surprised the Japanese, and let loose their torpedoes on the enemy fleet. It was very possible, their briefing officer had told them, that some of them would not come back alive. But after letting their torpedoes go, they climbed through the flak, and somehow managed to escape with their lives, although their planes were damaged.

Like many a returned veteran, Cooper plagues himself with questions about why did he get to return and live a full life with Elaine and raise three children, while others did not. One pilot from the neighborhood was shot down over Europe within a year after leaving for war, having had only a fraction of the training that Cooper received. A fellow Navy pilot with whom he switched assignments was killed on what was supposed to have been a routine mission. If they hadn’t switched, would Elaine now be a widow? These thoughts have haunted Cooper, one of the still surviving members of “the greatest generation.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com