By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—At the San Diego Model Railroad Museum you can enjoy trains that are 1/48 scale; 1/87 scale and 1/160 scale among others. As you walk along the large exhibit cases observing to-scale scenes of San Diego and the Southwest, you also can learn about a railroad woman whose persistence was a model for other feminists who wanted equal opportunities.

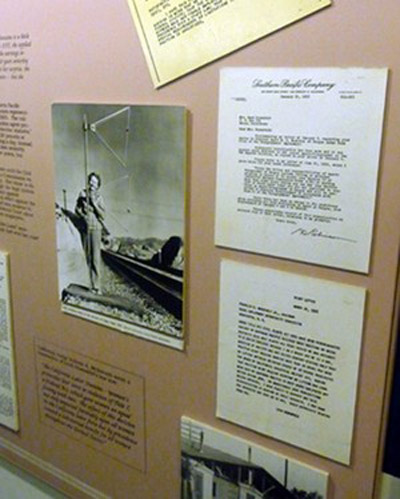

Her name was Leah Rosenfeld and although she had more seniority than the men who applied for the job of Southern Pacific station agent in Saugus, California (today part of city of Santa Clarita in Los Angeles County), she was denied the position. Southern Pacific said that the job would require her to occasionally work more than eight hours per day, and to lift articles weighing more than 25 pounds. California’s protective laws prohibited companies from giving jobs exceeding such weight and time limits to women.

According to a narrative board researched and written by Shirley Burman, Rosenfeld’s male-dominated telegraphers union wasn’t interested in coming to her aid. There was not much she could do about the matter until after Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race or sex.

Rosenfeld filed a complaint with the federal Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC), chaired in 1966 by Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr. The station master position, she wrote, was “denied to me and assigned to a junior employee because I am a woman and he is a man. The question of ability was not raised, the company stating only that position might require working more than 40 hours a week or lifting articles in excess of 25 pounds prohibited to women by California Industrial Act.”

She said that while Southern Pacific had used that “excuse” to deny better paying jobs to women, when it came to undesirable jobs, the “prohibition is seldom enforced.” She added that the discrimination worked a hardship against her; noting that “I pay the same for groceries as do men.”

In 1971, “California’s Protective Laws were declared unconstitutional; Leah had won her case,” the narration continued. According to Judge Rolleen W. McIlwirth, the decision not only helped the women of California, but by creating a precedent helped women throughout the United States.

The railroads did not treat women uniformly throughout its history—their hiring and promotion practices influenced by pragmatism and work force availability. As early as the Civil War, Abbey Strubel was working as a telegrapher, even though alarmists “feared that the physical stamina and nervous systems of women would be wrecked if they operated machinery,” according to the narrative.

“Isolated duty stations were preferred by many female operators because they were good places to raise children,” it went on to say. “They could keep their eyes on the kids and still do the jobs.”

In rural communities along the tracks, where trains did not make regular stops, “mistresses like Ina Adkins of Caliente, California, hung the outgoing mail on the mail crane to be grabbed by a hook on the moving post office car. After the train had passed she picked up the thrown off incoming mail.”

Englishman Fred Harvey in 1876 created a series of restaurants in Santa Fe train stations across the country, and “hired young girls between the ages of 18 and 30 of good character and who radiated an image of wholesomeness. The ‘Harvey Girls’ were more than waitresses; they were hostesses. The girls dressed in a simple black dress with a white neck collar and black bow with a starched white apron with no jewelry or make up. The Harvey Girls brought a civilizing influence to many communities with their good manners and social poise. Many married local ranchers, miner and railroaders.”

An offshoot of the “Harvey Girl” program came in 1926 with the establishment of “Indian Detour Couriers” – sightseeing guides who took passengers from trains on detour excursions to break up their transcontinental trips. The women guides were called “couriers” with preferred hires being “college-educated women who had a knowledge of native people, languages, culture and the landscape.”

In 1935, another opportunity opened for women as “registered nurse stewardesses” on passenger trains. “The duties were to assist women and children and to attend to the needs of the elderly on cross-country journeys. The nurses were known for their intelligence and candid friendliness. Babies and small children required extra attention. Formula had to be made and bottles warmed while games kept small children amused on long journeys.” Some railroads created programs in which little girls could be helpers as junior stewardess nurses.

Even before one enters the model railroad museum, one can pick up bits of railroading knowledge. On the bottom floor of the Casa de Balboa, which the museum shares with the archives of the San Diego Historical Society, one finds a semaphore—the old mechanical signaling device for railroads—with an explanation of how they worked.

The device standing besides the track had an upper and lower arm, with the top one telling about track conditions over the immediately upcoming mile-long block; and the lower about track conditions on the following mile-long block. The blade for the upcoming or “home block” was painted red; while the one for the “distant block” was yellow with a fishtail. Red, green and yellow lights in connection with each arm indicated whether the train should stop, proceed with caution or go.

Immediately inside the museum doors one encounters a scale model Cabrillo Yard on the right side of a walkway and the depiction of the San Diego & Arizona Eastern Railway exhibit on the left. Wending one’s way around the San Diego and Arizona Eastern exhibit takes one to the Tehachapi Pass scale model and to the Pacific Desert Lines exhibit.

A sign board informs that “construction on all layouts began in 1982” with some 300 club members volunteering on the average of one night a week to construct the railroad. The volunteers put in over 10,000 hours a year from 1982 to 1987.

“There are approximately 115 scale miles of track in all the exhibits,” said the sign. “This equates to about 6,560 actual feet or 1 ¼ miles” of model railroad, exclusive of the many feet of sidings and yard trackage.

Currently the San Diego Model Railroad Club is working on a diorama that will recreate in miniature downtown San Diego as it appeared in the 1950s. Club members are working from photographs in the San Diego Historical Society’s archives and from Sanborn maps showing the location of each building.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. This article appeared previously on examiner.com