-67th in a Series-

Exit 65, Boulevard, California ~ Rough Acres Ranch

By Donald H. Harrison

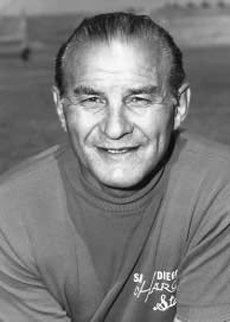

BOULEVARD, California—Whatever developers may someday build on the Rough Acres Ranch, it will be remembered by pro football fans as the place where San Diego Chargers Head Coach Sid Gillman decided to conduct the team’s 1963 summer training camp. Gillman ordered his team, which had compiled a miserable record of 4 wins and 10 losses in the 1962 season, to report to what was then a rural and primitive dude ranch for the express purposes of toughening up. The coach wanted his players to be far from the distractions of coastal La Jolla, where in the previous pre-season the team had trained on the UCSD campus.

In the preceding 29 years of his football coaching, Gillman had been celebrated as the father of the modern passing game. In 1963, the Jewish coach decided to pioneer at least two additional modifications to classic football. In what was then the era of the Civil Rights Movement, he committed himself to thoroughly integrating his team with seven black players, who bunked with their white counterparts according to field position.

Additionally, he introduced a rigorous weight training program, especially for linemen. For this purpose, he brought aboard Alvin Roy, who had been the coach to the 1960 U.S. Olympics weightlifting team. To bulk the football team up, Roy prescribed not only lifting weights but also eating three hefty meals a day, each meal accompanied by 5 milligrams of a pink pill known by the brand name Dinabol and by the generic name methandrostenolone. The pills contained an artificial form of testosterone. Today, they would be known and understood as steroids, illegal in professional sports. But that was the dawn of the steroid era, when they were legal and their effects little understood. Roy said the Soviet Union’s men’s weightlifting team used the pink pills for the 1960 Olympics in which they took a gold medal in six of the seven events. Bulking up the Chargers, he figured, would enable them to outmuscle opponents at the line of scrimmage.

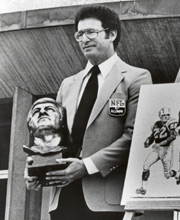

Some critics have said that because the Chargers linemen were “doped” by Roy, that was why the team would go on to win the 1963 American Football League (AFL) championship with a thrilling 51-10 victory over the Boston Patriots. One who disagrees is Ron Mix, who was later inducted into the pro football hall of fame and the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. He played on that team and led a player’s revolt against use of the pills.

In an e-mail exchange with San Diego Jewish World, the former offensive tackle and Jewish community member said the Chargers’ 1963 championship was attributable to superior coaching and to on-the-field talent. Mix related that the team had only been taking the pills for approximately five weeks when he learned of their possible harmful side effects. He called a team meeting and informed the players and the vast majority of them stopped taking the pills. Mix said he could recall only a couple of players who continued and none of them were starters on the team. He said any benefit to taking Dianabol would have worn off long before the regular season started.

He said Gillman, who died in 2003, “had a group of assistant coaches that were stars in their own right: (1) Chuck Noll, later a Hall of Fame coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers; (2) Al Davis, later a Hall of Fame owner-coach, general manager of the Oakland Raiders; (3) Bum Phillips, later Head Coach of the Houston Oilers; and (4) Jack Faulkner, later Head Coach of the Denver Broncos. In addition the Chargers had one of the top directors of player personnel, Don Klosterman. All these men were hired by Sid Gillman.”

Furthermore, said Mix, an attorney now residing in San Diego, the talented Chargers squad included Tobin Rote; Hall of Famer Lance Allworth; All-Pro quarterback John Hadl; offensive tackle Ernie Right, who was “340 pounds of mean;” defensive end Earl Fasion who was also “mean,” 280 pounds worth; and Mix himself as an offensive tackle. Mix declared that “Earle Ladd and Earl Fasion played their positions as well as anyone ever played and would both be in the Hall of Fame if injuries had not shortened their effective careers.” Additionally, he said, no one should forget “two of the best running backs of all time, Paul Lowe and Keith Lincoln.”

In Mix’s view, although Gillman believed the team’s success was due to “isolating the team in Rough Acres, the truth is we won despite Rough Acres.”

He said that the Rough Acres Ranch consisted of “a mess hall, about 40 one-room shacks (yes ‘shacks.’) It would be an exaggeration to call these facilities ‘ranch houses.’ They were small, made of wood, no air conditioning, so small that players were assigned two to each shack and slept in bunk beds. (no misprint bunk beds!)

“The practice field was so rough and hard that grass could barely grow and the entire field had to be covered in sawdust,” wrote Mix, apparently living the nightmare all over again. “There were no indoor showers—a slab of cement was laid, surrounded by a mid-sized fence and players showered outdoors.

“During our eight weeks there, a total of between 15 and 20 rattlesnakes were killed.

“The food was perhaps the worst I have ever had at a training camp. Wait I need to change that: it was the worst I have ever had before or since.

“Sleep was difficult because, as I said, there was no air conditioning in the shacks but there were enough holes in the wooden walls to admit mosquitos and the desert heat did not seem to diminish much in the evening. Bad food and lack of sleep do not present ideal conditions to mold a team.

“To me, Rough Acres was a negative. The players took things into their hands by causing enough damage to the ranch that the owner sued the team and declined to rent the ranch again to the team.

Summarizing, Mix said, “the positives, however, outweighed the negatives. And the positives were that we were a team that because of weight-training was the strongest team in professional football; we had the smartest coaches, and we had superior talent.”

ESPN writer T.J. Quinn wrote in 2009 about the use of steroids by the 1963 Chargers, quoting Mix extensively. He noted that Mix was then the team captain and a four-year veteran of the AFL. Mix said a doctor was shocked to learn what the players were taking, and showed them the literature about the pills. Said Mix:

I still remember what it says. It was in big red letters. It said, ‘Dangerous. Not to be taken over extended periods of time, will cause permanent bone damage, liver damage, heart damage, testicle shrinkage.’ Now comes the obligatory joke,” Mix says. “The other three we could live with. But the last — no!”

…”[Roy] was a very knowledgeable guy. Unfortunately, apparently, he had a major character flaw,” Mix says. “And that character flaw was [that] he wanted results. He didn’t care how you got the outcome of the results. And, if the outcome of the results included using something that had the potential of being dangerous, he endorsed it. Hence the Dianabol.”

Mix spoke up against mandatory use of Dinabol during a team meeting prior to the regular season. Thereafter players no longer were required to take them, although some did–at least until 1970, according to Quinn.

Steroids were banned by the NFL in 1983, two decades after the experiments at Rough Acres Ranch.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com