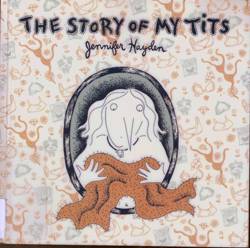

The Story of My Tits by Jennifer Hayden; © 2015; Top Shelf Productions; ISBN 978160-3090544; 340 pages; $29.99

Story by Donald H. Harrison; Photo by Shor M. Masori

SAN DIEGO –When she was a young teenager, Jennifer Hayden was frustrated that she had remained flat chested while many of her classmates had already bloomed. But eventually her breasts grew. She admired them as a badge of her femininity, an emblem of her womanhood. She enjoyed them being admired and fondled. Later, she had children, and they nourished. And then, just as her mother’s did before her, one of her breasts developed cancer. Her mother had a single mastectomy, but Jennifer, fearing the cancer might spread, chose to have a double mastectomy. Afterwards, she felt she had come full circle: flat-chested again.

With more than 1,300 illustrated panels, some worthy of many minutes study, this autobiography tells not only of Hayden’s “tits,” but also about family relationships, or in some cases the lack of them. For example, when her mother developed breast cancer, her father—well into an affair with another woman—was emotionally unavailable. Her mother had long known about the affair but kept her pain internalized, never sharing with her family.

Disgusted with her father, despairing over her mother, Hayden moved in with Jim, her college boyfriend, and notwithstanding poverty—he was a musician and she was a freelance writer—they stayed and grew together, their partnership even withstanding moving as a couple into the home of his parents, where she wondered whether she would ever be married and have a home of her own.

While Hayden’s breasts are a “vehicle” for telling the story of her life, as well as that of her mother, her autobiography is far more fully developed. She tells of some of the adventures she and Jim shared, the experience of pregnancy, childbirth, and parenthood, and of bonding with Jim’s mother, Alice, who, unlike her own mother, was interested in every aspect of Jennifer’s life. It was a tremendous blow when Jim’s father, and later his mother, died, the latter a victim of lung cancer.

Later, when Hayden was diagnosed with breast cancer, dark thoughts descended upon her, and she agonized over what and how she should tell her children. The thought of her death haunted her, but she survived, eventually had breast implants, and she turned from writing to drawing, which had been a forgotten childhood love.

The drawings are in black and white; Hayden represents herself as having a needle nose and unruly hair. Some of the drawings and wording are sexually explicit.

*

Having that background from reading her book, I arranged to meet at Comic-Con with Hayden, who had been invited there to speak and sign autographs. I asked if it were hard for her to put such an intimate story out there for public consumption.

Having that background from reading her book, I arranged to meet at Comic-Con with Hayden, who had been invited there to speak and sign autographs. I asked if it were hard for her to put such an intimate story out there for public consumption.

“I have always been a very open person,” she responded. “I have been criticized for it and complimented for it, both. But I am anxious that when things are in me, I have to get them out, and I found over the years that everyone has the same junk that I do, so for me it’s not as much a privacy issue as it is for other people. I think that there is almost an arrogance in being super-private. What makes you think that your problems are so amazing?”

The process of writing an autobiographical novel is “just digging for the truth and the fact that you are digging in your own crap pile doesn’t bother you because there’s the knowledge that you are going to find gold somewhere. Actually you know you are going to reach through to the universal things, which makes it art, and you find your best access to the universal thorough your own pain…”

When she was preparing for her surgery, she related, ”something in me said ‘if you don’t go now, if you don’t get this out now, you’ll never do it.’ It was almost kicking me to get going. Previously I might not have been able to draw a graphic novel, or write one, but … I knew that I had this perfect story that had landed in my lap that was going to say everything I wanted to say about life.”

Other graphic novels had been written and drawn about overcoming breast cancer, including Cancer Vixen by Marisa Acocella Marchetto and Mom’s Cancer by Brian Fies, so Hayward knew that it would be important to cover different ground – dealing not only with the loss of breasts, but also with what they mean to a woman.

“I loved mine,” she said. “They were great play things, great sex orbs, great confidence givers. They become very wrapped up in your identity when you are younger and when you have babies, but the bottom line is if you are deprived of them, you had all those things already. It’s like going to the Wizard of Oz to get a set of boobs and he says ‘you had them all along.’”

She told me that she has received a variety of reactions to her book. From other breast cancer survivors, Hayden often hears appreciation for putting their feelings, hopes and fears into context. Some typical comments were “My mother went through breast cancer but I never was able to put into words what I felt about it, and then I read about you and your mother” or “I just came back from a lumpectomy and I am so scared and I read your book and it made me feel better.”

She also has had some adverse reactions from people who think the word “tits” doesn’t belong in any book title, on the one extreme, and on the other, “when some guys come by a show and think it is porn, and I say ‘yeah, buy that. Read that, buddy, you need it.”

Asked how she responds to those who dislike the word “tits,” she responded that she gave a lot of thought to whether she should call them tits, tatas, boobs, or breasts before deciding that “tits” seemed right for the kind of “humor and lovingness” with which the book is infused.

In telling her life she had to discuss some of her family’s challenges and failings. “Obviously I did crack a few eggs to make this omelet, but I think the ones I really cracked, forgave me because they understood.”

Calling The Story of My Tits an autobiographical novel seems almost a contradiction. If it’s an autobiography it’s supposedly all true, not a word of fiction. If it’s a novel, it’s made up. Could her story be both?

Hayden noted that she draws herself with a carrot nose, that like Pinnochio’s becomes progressively longer. Could that mean that there are a few fibs in there? She laughed, not at all self-consciously. “It’s a possibility,” she said.

*

Harrison is editor and Masori is a staff photographer of San Diego Jewish World. Their emails are donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com and shor.masori@sdjewishworld.com, Comments intended for publication in the space below MUST be accompanied by the letter writer’s first and last name and by his/ her city and state of residence (city and country for those outside the United States.)