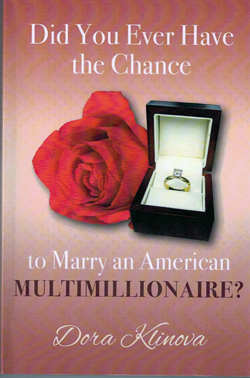

Did You Ever Have the Chance to Marry an American Multimillionaire? by Dora Klinova; DK Corporation; (c) 2016: ISBN 9781533-137852; 245 pages.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO — This autobiographical work was fictionalized enough to be classified as a novel, but it closely follows author Dora Klinova’s own progress in San Diego in the 1990s as a refugee from Odessa, Ukraine, in what was then the Soviet Union. She tells with great attention to detail how “Della” met, was courted by, and had a long-lasting intimate relationship with “Herbert,” the widowed owner of a strip mall, which included a large restaurant space. And did she ever have the chance to marry the American multimillionaire? The chance, yes.

SAN DIEGO — This autobiographical work was fictionalized enough to be classified as a novel, but it closely follows author Dora Klinova’s own progress in San Diego in the 1990s as a refugee from Odessa, Ukraine, in what was then the Soviet Union. She tells with great attention to detail how “Della” met, was courted by, and had a long-lasting intimate relationship with “Herbert,” the widowed owner of a strip mall, which included a large restaurant space. And did she ever have the chance to marry the American multimillionaire? The chance, yes.

Today, when we say someone is a millionaire, or even a multimillionaire, it is perhaps not such a big deal as it was 20 years ago, especially not in San Diego where rising real estate values have propelled many of middle class status into the millionaire class. One shouldn’t get the idea that Herbert, or as the author called him “Herbertchik” was a Daddy Warbucks figure. The first two times he escorted Della, or as he called her “Dellishka,” out for a meal it was to a Marie Callender’s franchise. On another occasion, when they went clothes shopping, it was at a Kmart.

But the couple moved up in luxury, celebrating two separate New Year’s Eves at the Hotel del Coronado and other occasions at the Marriott Hotel adjacent to Seaport Village. They also went together to the Opera, enjoying Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, as well as an off-Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof, which Della, herself Jewish, enjoyed very much. However, she couldn’t help but notice that in the stage production, one of the women prepares tea with a tea bag, something that would have been uncommon, if not unknown, in the 1905 Russia of storyteller Sholem Aleichem. In those days, Della notes, the tea was boiled in a samovar and then poured out into a plate, from which it was noisily slurped. Sticking to history could have provided some funny scenes, she told Herbert.

In addition to going out frequently for meals and for musical entertainment, Della and Herbert also made periodic trips to Las Vegas. Initially she was delighted and bewildered by the flashing lights and ringing bells of the slot machines, but she grew used to the artificial hubbub and eventually became bored by it.

While America offered many delights and an easy-going, pleasure-seeking lifestyle that most Ukrainians could only fantasize about, uprooting from home and changing nationalities proved nevertheless difficult for Della. “A torrent of new events and a volcano of emotions, admiration and disillusion, trust and betrayal, support and ignorance, love and displeasure, appreciation of new wonderful friends and disappointment in old ones, supense, frustration, perseverance — emigration means all of these, plus much more,” author Klinova noted at one point.

For ex-Soviet citizens, even those who clung to their Jewish identities, religion was sometimes an odd admixture. For much of their lives, Soviet citizens were discouraged, when not outright forbidden, from practicing their religion, and thus came to have an imperfect understanding of what it was to be a Jew. For Della, Jewish experiences not only meant worshiping at Temple Emanu-El, a well established Reform congregation in San Diego, but also exposure to groups outside the Jewish mainstream such as the “Jews for Jesus” movement, and the Self-Realization Fellowship. Somehow she integrated all of them into her religious consciousness.

Although Della and Herbert appeared to love each other deeply, their relationship developed problems which author Klinova dramatizes and later analyzes. If couples were to read this book together, it would be interesting to see how many agree with the author’s interpretation of those things that went wrong, and how many would take the contrary position. Did the fault lay with Herbert’s idiocyncracies or with Della’s unwillingness to accommodate them? Would opinion divide by gender, or perhaps by a person’s nationality at birth?

Klinova has an interesting writing style. I particularly enjoyed those passages in which we can “hear” Della’s thoughts as she first frames questions about her situation, and then goes about answering those questions, sometimes in ways that we might not expect. For San Diego readers, Klinova’s descriptions of well-known venues in the San Diego region are an added treat.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com