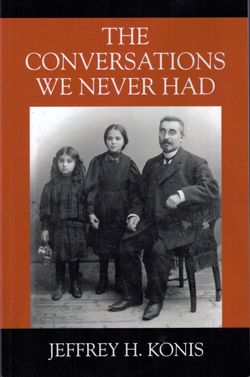

The Conversations We Never Had by Jeffrey H. Konis; Outskirts Press; © 2016; ISBN 9781478-767299; 197 pages; $13.95.

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – On the back cover of this book is the listing “Fiction: Historical” and that, perhaps, constitutes the author’s greatest regret. If he could have gone back in time, the listing would have read “Biography.”

SAN DIEGO – On the back cover of this book is the listing “Fiction: Historical” and that, perhaps, constitutes the author’s greatest regret. If he could have gone back in time, the listing would have read “Biography.”

While in law school, author Jeffrey H. Konis lived conveniently in the apartment of his adoptive grandmother, Olga Konis, who in actuality was his great-aunt. Her sister, Sonya, had died, leaving her son, Eber, a teenage orphan. After some hesitation, Olga and her husband, Bonya, decided to take Eber with them to America, rather than seeing him sail to an uncertain future on a ship bound for Palestine. Eber later became Jeffrey’s father.

Author Konis lacerates himself for being too preoccupied with law school—and its attendant parties—to pay his grandmother more than cursory attention, even though he lived with her in her apartment. Two aides took care of Olga’s physical needs during the day and evening, while Jeffrey was there—just in case—during the overnight hours. While there has been numerous opportunities for Olga and Jeffrey to hold substantive conversations about his grandmother’s life, as well as about his father’s early years, Jeffrey failed to take advantage of the opportunity.

The Conversations We Never Had is an imagined story, pulled together from hints, short threads of conversation, his grandmother’s casual comments, and Konis’s reading about the Holocaust years.This was supplemented by his father’s not very explicit memory of events that had occurred during the same period.

The narrative takes the form of conversations between Jeffrey and Olga, in which she tells of growing up in Eastern Europe; her love and juvenile rivalry with Sonia who was five years her senior; visits to Berlin and her life in Paris, where she started—but never got to complete—her studies of medicine; her experiences in the Holocaust, and her disapproval of intermarriage.

The latter two topics are the most engaging. In his treatment of the Holocaust, Konis imagined a scene in which a German guard has misplaced her clipboard, and Olga volunteering to help find it. The guard told Olga if she didn’t find it, there would be consequences for her failure. Unfortunately, Olga found the clipboard stuffed into the clothing of another inmate, a Polish woman. She asked the woman to return it, but was scorned, and as her time limit was elapsing she indicated to the guard where the clipboard was hidden. The other prisoner was escorted from the factory and later executed. Did Olga feel guilty? Was this just an unfortunate matter of survival? In his novel, Konis examines the question.

Similarly, he delves deeply into the question of intermarriage. Even if a non-Jew converts to Judaism, the grandmother argues, won’t her children still look upon intermarriage as a natural course of events. Maybe not in one generation, but perhaps in two, will such a family completely lose its Jewish identity? Olga makes the case for marrying within one’s own religion—an argument that has been ignored by more than a majority of American Jews of marriageable age.

While the conversations are fictional, the issues discussed in this conversational format are quite relevant, making The Conversations We Never Had well worth reading.

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com