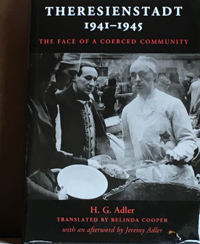

Theresienstadt 1941-1945: The Face of a Coerced Community by H.G.Adler; Cambridge University Press, 2017

By Dorothea Shefer-Vanson

MEVASSERET ZION, Israel — This monumental monograph, to which no book review can hope to do justice, comprises more than 850 pages and constitutes a far-reaching and detailed account, or rather scientific analysis, of the concentration camp that was located in what was known by the Germans as the Protectorate and today is the Czech Republic. The book was first published in German in 1955 and a revised edition in 1960. Only recently has the long-awaited English version been made available to the general public.

MEVASSERET ZION, Israel — This monumental monograph, to which no book review can hope to do justice, comprises more than 850 pages and constitutes a far-reaching and detailed account, or rather scientific analysis, of the concentration camp that was located in what was known by the Germans as the Protectorate and today is the Czech Republic. The book was first published in German in 1955 and a revised edition in 1960. Only recently has the long-awaited English version been made available to the general public.

The author, who was himself incarcerated in Theresienstadt from 1942 to 1944, was known before his deportation there as a poet, novelist, and scholar. In this book he has produced a seminal work that is generally devoid of personal reminiscences but rather undertakes an exhaustive and objective study of the various aspects that went into the making and maintenance of the camp, focusing systematically on such categories as the history, sociology, and psychology of the camp (or ‘ghetto’ as it came to be called at a later stage). Within each of these major categories there are subdivisions into such subjects as deportations to and from Theresienstadt, administration, population, housing, nutrition, labor, economy, legal and health conditions, to name but a few. Each section, chapter, and category is accompanied by extensive statistical data, original source-material, personal accounts, and documentary evidence.

The somewhat incongruous photo chosen for the cover illustration shows a prisoner wearing a cook’s uniform giving out food in the ghetto courtyard to a newly-arrived transport of Dutch Jews. It seems somewhat strange at first, considering the general insufficiency of food in the camp, but this fits into the façade of normality that the camp was designed to convey. The ‘normality’ of the camp was, however, a sham created by the Germans, who ruled a society based on violence, intimidation, and a set of warped ‘rules and regulations’ governing the lives of the unfortunates imprisoned there.

Adler traces the history of the camp from its initial inception by Himmler and Heydrich as ‘a city peopled by Jews’ to its functioning as a place of imprisonment for thousands of individuals brought primarily from the Protectorate and the Reich. Many of those sent there were considered to be privileged because of their service in the German army in WWI or special social or intellectual status. Adler describes the horrors experienced by those deported there in cattle cars or passenger trains followed by the initial processing procedure. The new arrivals had to undertake a three-kilometer walk to the camps from the railway station of Bohusovice, carrying their luggage and supervised by SS men who often used violence to get their victims moving. Having arrived at the camp the prisoners were instructed to leave their luggage at the processing center (the Schleuse), where wholesale confiscations and theft were rife, perpetrated by both the SS and dishonest Jewish inmates.

Acceptance of the inadequate and poor quality rations constituted the next step in the process of ‘acculturation,’ and many new arrivals were unable to tolerate the meager and unsavory victuals. Adler likens arrival and processing at the camp to birth, a passage from one state of being to another, and one that is generally accompanied by crying. He describes the mental anguish and process of debilitation experienced by new arrivals, and by elderly persons in particular, many of whom rapidly descended into mental conditions akin to dementia and/or hysteria, as well as a form of apathy that soon led to death.

Accommodation and sanitary conditions in the camp were substandard in the extreme, disease and vermin of all kinds were rife, and the overcrowding meant that privacy and hygiene were simply out of the question. Certain individuals were able to benefit by being appointed ‘room elders’ or even ‘camp elders,’ and in many cases, according to Adler, these Jews exploited their superior position for personal gain and comfort. Welfare and medical departments were set up, supposedly to care for the prisoners, but there was little that could be done in view of the paucity of the equipment and medicines available. Work of one kind or another was required of all prisoners, and those who complied with this were given extra rations. The threat of inclusion on one of the transports to an unknown destination in the east (usually Auschwitz and the gas chambers) was

ever-present.

In one of the last chapters of the book Adler describes the vibrant cultural and artistic life that prevailed in the camp, perceiving it as an illusory way of escape from the grim reality of the situation. Most of the camp’s leading artists, musicians, actors, and writers were deported to Auschwitz and murdered there as the end of the war approached. This was also the fate of many of the ‘camp elders’ who had previously benefited from the preferential treatment accorded to them by the SS. The overall impression given by this book is of the prevalence of depravity and misery that seems to have been an almost inevitable adjunct of the general situation in the camp.

In addition to an index, the book also includes a chronological summary of the salient events on a day-by-day basis, as well as two hundred pages detailing sources and literature. Special credit should go to Belinda Cooper, whose translation from the original German reads fluently and well. As an account of an abominable episode in human history, this book constitutes a milestone of objective dedication to recording every aspect of this ‘experiment in evil.’

*

Shefer is an author and freelance writer who may be contacted via dorothea.shefer@sdjewishworld.com

Well done Belinda Cooper! It is high time that Adler’s definitive work on Theresienstadt was translated into English. Fact is, I felt strongly enough about that gaping hole that last year I had even considered banging out a translation myself–knocking out maybe a page or three a day–until I heard from a colleague here that one was already “in the pipe.”

So, once again, thank you Ms. Cooper!